Displacements

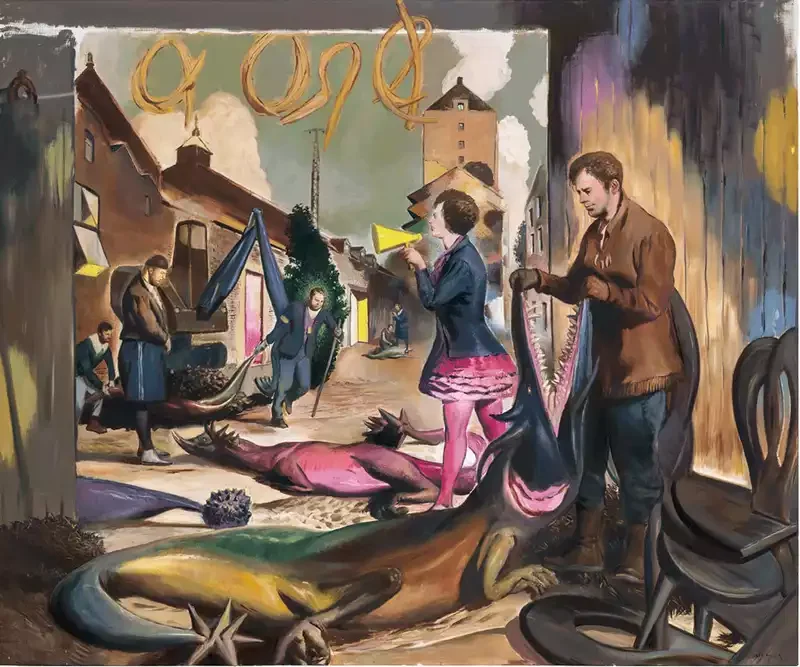

/In the painting by Giovanni Bellini known, by one of its names, as “St Francis in Ecstasy” (c. 1475-1480), a curious lack of visual references to Francis’ stigmatisation has long puzzled art historians. The saint is depicted in the midst of a rocky landscape on the outskirts of a city. In the immediate foreground is a grotto; at the grotto’s opening is a makeshift oratory, overgrown with creeping ivy. Francis stands with his back to the oratory, face tilted upward and arms outstretched, looking toward the sky and out over the valley below, as sunlight pools on the surface of the rock behind him. A few paces away from the grotto is Francis’ donkey, looking in the same direction as the saint.

Giovanni Bellini, St Francis in Ecstasy, c. 1475-1480, Frick Collection, New York City.

That is the whole scene. Unlike conventional portrayals of Francis’ stigmatisation, Bellini’s painting contains few references to the wounds piercing the hands of the saint: while there are faint red marks staining Francis’ palms, there are no markings on his feet, nor on his chest. There is also no hint of the angels usually pictured together with Francis at the moment when he receives the stigmata. All is still. There is very little, in fact, to suggest that anything extraordinary is taking place. Yet the painting itself is far from unremarkable. While it was common, during the fifteenth century, to paint the ecstasy of Francis as taking place outdoors, Bellini gives the landscape special attention. Francis is painted in the open air, surrounded by the elements: rocks, vegetation. Bellini has depicted the latter in vivid detail, exulting in every veined leaf and textured rock; the other name of the painting is simply “St Francis in the Desert.”[1]

What is the subject of this remarkable painting? Images in Christian mysticism are often complex, containing more than a single layer of meaning. One interpretation is that Bellini here has combined visual references to the stigmatisation with cues pointing toward that other famous instance of ecstasy in the life of Francis, the moment when, looking in rapture to the skies, Francis composes the Hymn of the Sun. This interpretation has been resisted on the grounds that Francis’ attitude in the pictures is “receptive” rather than “creative,” and yet an attitude of wonder and openness corresponds very well with the Hymn’s sentiment: “[e]ven if one does not agree that Francis is bellowing out a song, there is compelling reason to accept that he is looking in a state of inspiration to the sun, and that is the manifest relation between Bellini’s and the saint’s attitude toward nature.”[2] Landscape painting in Italy owes a debt to Francis’ celebration of the environment, and Bellini certainly viewed landscape painting as a religious expression. In Bellini’s painting, then, what we see is Francis receiving his wounds as he delights in the sun’s warmth, approaching the sun respectfully in its role as source of all life, as the opening lines of the Hymn form in his mind: “praised be Thou...honoured brother Sun…”[3]

Moreover, Francis is not the only creature - nor the only animal - looking up in rapture at the sun, which shines not on Francis alone but on several parts of the landscape. There is the donkey, whose head is facing the same direction as Francis’, but there are also the stone walls of the city in the background, and the rock of the grotto, both basking in the sun’s glow. Finally, there is the tree in the upper left-hand corner of the canvas, occupying the position in which we would expect to see the angels come to deliver the stigmata. The boughs of the tree bend in toward the centre of the canvas, anticipating perfectly the backward-arching posture of Francis, suggesting the same attitude of receptivity (this same bending curve is repeated also in the illuminated part of the rock we see above Francis, again suggesting an anticipation of Francis). In fact, compared to the landscape, Francis appears to stand somewhat out of the light, with the mountainside and crevice plants receiving the majority of the sun’s warmth.

By painting the landscape itself as enraptured, Bellini is alluding to an old tradition, stretching back to the Psalms, of plants, animals and critters described as praising God and participating in a creature-communal liturgy.[4] This was an idea especially emphasised by the Franciscans, who often looked to nonhumans as spiritual models. Thus Roger of Provence, one of the earliest Franciscan mystics, writes in his Meditations, “even now as you withdraw yourself from God, all other creatures approach him and draw near to him. Do they not condemn you?”[5] Franciscan spirituality suggests a humanisation of the environment, but equally a dehumanisation of the spiritual and an inversion of the hierarchy that would situate animals but also plants, rocks and “inanimate” life further away from God than humans were thought to be.[6] What is extraordinary about the painting known both as “St Francis in Ecstasy” and “St Francis in the Desert” is not only the attention given to the landscape on this astonishing canvas, in which the landscape is not a mere backdrop to a religious scene but the latter’s ground and motivation. It is also the way in which the landscape itself exemplifies the ecstasy depicted. For it is not Francis alone who “contemplates” the sun, receiving its light in a state of rapt attention and pleasure; it is just as much the donkey, the plants and the rocks who are engaged in contemplation.

Simone Kotva

[1] The painting entered the Frick Collection in 1915 under the title “St Francis in the Desert.” On the history of the painting and its interpretation, see Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, Jinyu Liu and Adam Gitner, “The Joy of St. Francis: Bellini’s Panel in the Frick Collection,” Artibus et Historiae Vol. 28, No. 56 (2007): 231–56. The interpretation I develop here is indebted to the brilliant essay by Anthony F. Janson, “The Meaning of the Landscape in Bellini's ‘St. Francis in Ecstasy’,” Artibus et HistoriaeVol. 15, No. 30 (1994): 41-54, and to the thought-provoking piece by Therese Sjøvoll that first brought the painting to my attention: “Kunst: Giovanni Bellini, ‘Den hellige Frans i ødemarken’,” St. Olav, Vol. 3 (2021): 40-43

[2]Janson, “The Meaning of the Landscape,” 52.

[3] Francis and Clare: The Complete Works, trans. Regis J. Armstrong and Ignatius C. Brady (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1986), 37-38.

[4] Elizabeth Theokritoff, “Creator and Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Theology, eds. Mark Cunningham and Elizabeth Theokritoff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 63-78.

[5] The Earliest Franciscans: The Legacy of Giles of Assisi, Roger of Provence, and James of Milan, trans. Kathryn Krug (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2015), 44.

[6] Giorgio Agamben, The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life, trans. Adam Kotsko (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013), 111: “If on the one hand animals are humanised and become ‘brothers’...conversely, the brothers are equated with animals…”