Last and First Men

/Jóhann Jóhannsson’s posthumously released film Last and First Men based on the novel with same title by Olaf Stapledon takes the form of messages sent to us from a very distant future. 2000 million years beyond our time, our descendants have suffered, triumphed, lived through eons of boredom and sudden bursts of brilliance. They have evolved through many generations into a series of new species, descendants of humans, interested in and feeling akin to us, however far removed they are from our lives.

Even if this fantastical tale is nothing more than that, a creative speculation on the edges of what even science fiction usually deals with, it raises a fundamental question: Can we grasp the perspective, the time frame of such an utterly distant future?

On the one hand, we often say things like “I cannot even begin to fathom …”, or “I wouldn’t even suggest I understand”, and we then only refer to very relatable scenarios such as illness, pain, and grief. Nothing could be more common, more human and unavoidable.

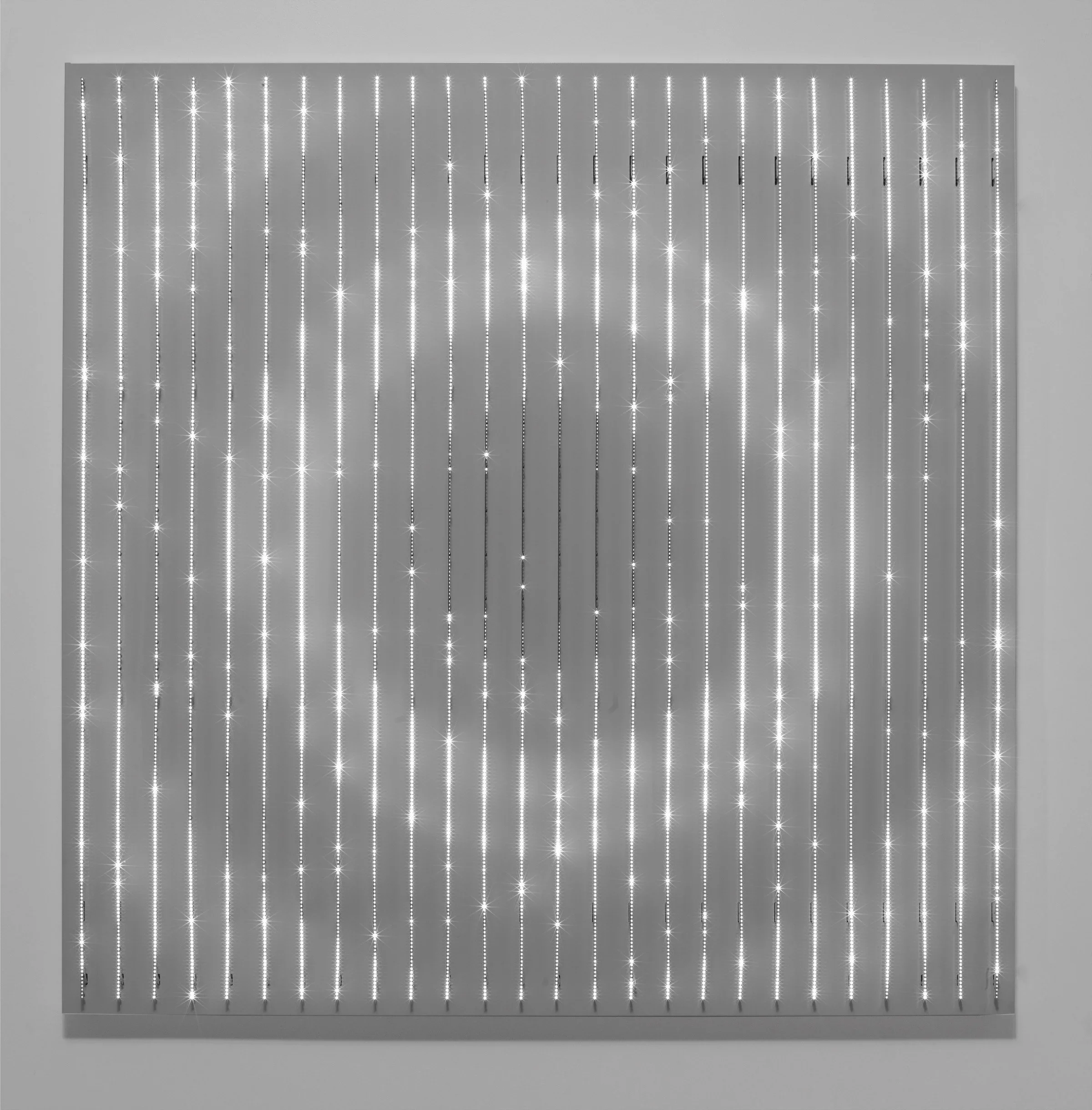

The time scales of the universe are related to its physical scale, one of those always known facts that we do not think of, that we only might consider when in the presence of a starry sky, or if we have chosen astronomy as our hobby or profession.

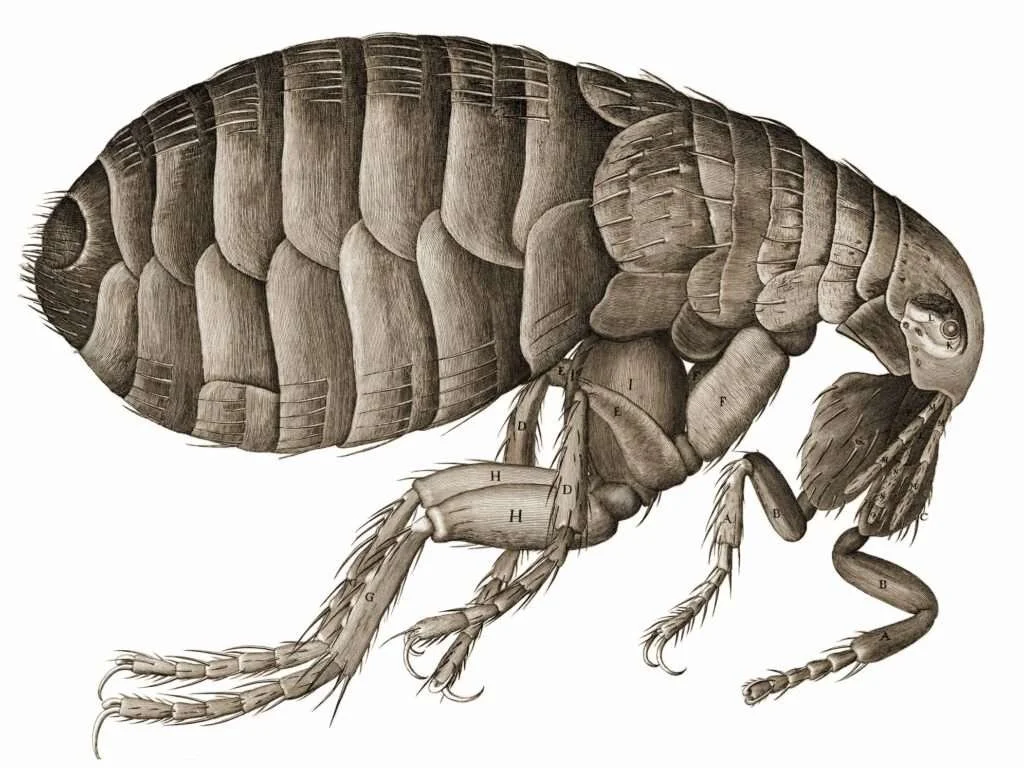

Our distant descendants in Stapledon’s tale have developed a special organ, situated at the top of their heads, which give them a sense directed at the sky above them. A limb suited to the awareness of the universe. Suitably, they also have a caste of astronomers inhabiting the highest floors of their immense buildings, reaching through the atmosphere to get a better vantage point for their observation of the beyond.

But without evolving similar organs, are we unable to understand what lies above our heads, above the clouds, and in fact all around us in every direction, beyond even the distant horizon where the laws of the universe forbids us to see?

What is it too know something? What is it to understand? Our meditating friends spend significant portions of their lifetimes focusing on a single everyday object: a flame, a sound, their own breath. Our contemporary astronomers have already built interplanetary robot observatories that float between us and the Sun, peering into the secrets of the cosmos.

But even these extraordinary members of our species will without question agree that they only know very little. Knowledge is always partial, always restricted.

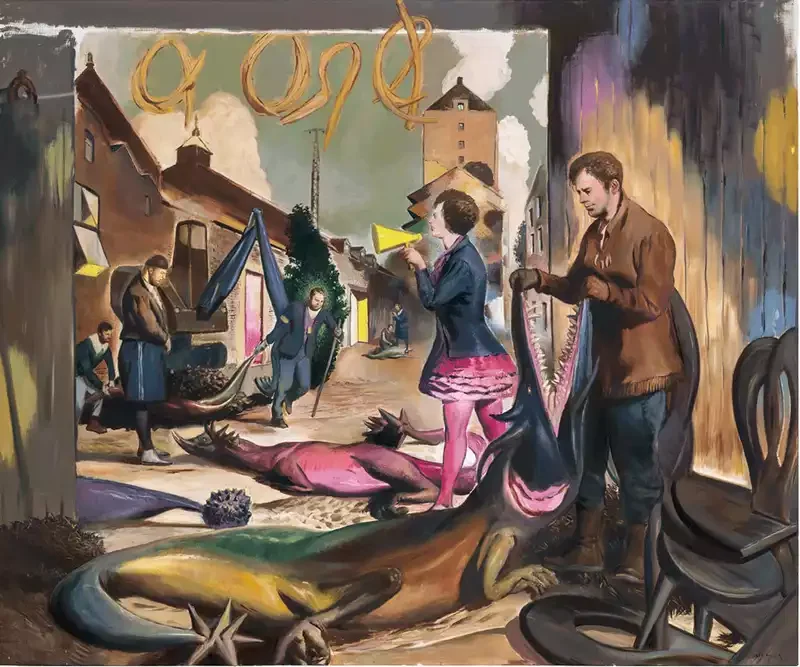

Perhaps is it the connection that art – like music, pictures, a movie with voiceovers – that is our best attempt at reaching those unfathomable perspectives, thoughts, realities and fictions.

It is in the absurdly limited experience that we humans are capable of, that we can at the same time reach our unlimited potential in grasping the ungraspable.

Tormod Otter Johansen