Weak States in Time of Plague

/Winner and Waster is a Middle English poem dating from 1352 or 1353, in the immediate aftermath of the Black Death, which first broke out in England in 1348. The title gives away the game: it is a dialogic poem, an argument between two characters—Winner, a representative of frugality, land acquisition, and, in his way, the empowerment of the mercantile class and Waster, a profligate who argues that the higher classes must spend, spend, spend. Only in doing so can wealth circulate and be put in the pockets of the poor. Lest this sound like Keynesians at battle with advocates of trickle-down economics, it is no such thing. The poem represents a debate within the system of feudalism, within the bounds of, at most, an emerging capitalism still mired in various modes of noblesse oblige.

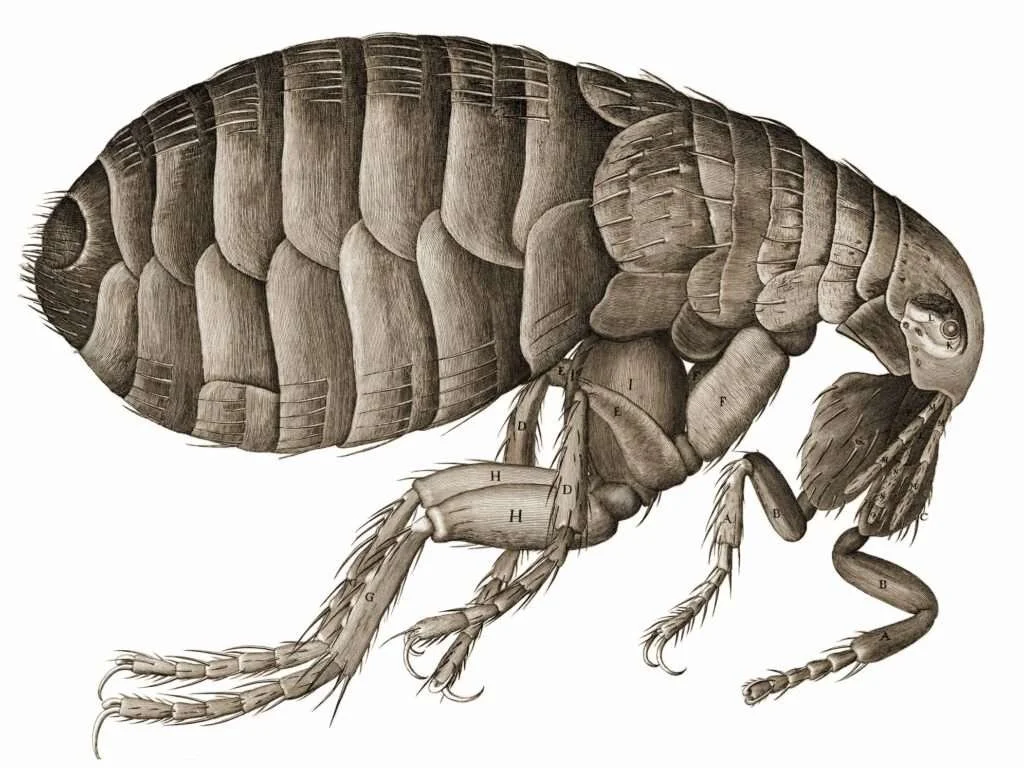

In the aftermath of the Black Death, medieval polities dithered, not knowing how to react. Laborers demanded the ability to move and seek higher-wage (and how new was the idea of a “wage”!) employment, the plague having killed between one-third and one-half of the population. Labor was in demand and so, by their lights, labor could now make demands. The English regime reacted by trying to fix prices; it passed the Sumptuary Laws of 1363, attempting to deny the upwardly mobile the right to wear certain fabrics and colors. In doing so, Edward III and the aristocratic class hoped to maintain strict class boundaries. The world, of course, was changing around them.

Philip le Bel

There was, in those days, only the faint glimmer of what we would now call “the state.” There were instead complex sets of obligations between families and classes, complicated multipolar interactions that propped up this lord here and that one there. The closest thing to a centralized authority was the Catholic Church, and even this found its authority refracted through its thousands of dioceses, religious foundations, and universities. The “king” was, per Kantorowicz’s famous phrasing, of two bodies—both a man and an office. But he was only, at this time, eking toward real power; the title merited more respect than the individual swathed in the robes of “state.” It was only in the eleventh an twelfth centuries that Capetian kings of France, for example creeped from being “reges Francorum” (Kings of the Franks) to “reges Franciae” (Kings of France). Their power went, in other words, only slowly from being that of a tribal protection of a people, to being that of authority over a place and those within its bounds.

In fact, taking France as our example (as it is perhaps the closest to a modern “state” any medieval kingdom came), we see the first successful attempts of centralization only a few decades before the outbreak of the Black Death. On September 14, 1307, King Philip IV of France (that is, rex Franciae, not Francorum) ordered the mass arrest of Knights Templar by royal officials. The letter bearing the bad news is curious—it does not demand their arrest merely on the grounds of his own authority; rather, it argues that the infamy (“fama”) of Templars’ lewd acts has become so great that the local papally-appointed inquisitor, William of Paris, has had no choice but to begin an investigation. It was only on account of this investigation that Philip had acted. He was acting legally, not tyrannically. William, playing his part as an agent of the king’s, wrote to major Dominican officials throughout France only a few days later, on September 22. His wording gives the game away:

Therefore, the aforementioned lord the Most Christian King, after hearing those previously stated accusations, terrified with the stupor of wonder and burning with ardor of the faith, did not reject them, but diligently related the things he had heard both to us and to his secret counselors and to our most holy lord the highest pontiff, first at Lyon and then at Poitiers. (Field, The Beguine, the Angel, and the Inquisitor, 75).

William makes it sound like the pope and the king are in agreement, that they had both been moved by the horrors circulating about the Templars. This is, however, not true. The pope, it would turn out, was caught off guard by the entire affair. There were no significant rumors about the order. Philip and William are constructing a legal justification for their actions, that is, they are simultaneously bureaucratizing government and providing their actions a veneer of legality. In one fell swoop, they hope to crush the king’s enemies and sell his rule as legitimate and just. And it worked! On October 13, 1307 (the origins of our spooky superstitions about “Friday the Thirteenth”), royal agents arrested, tortured, and forced confessions out of the Templars in France.

The pope, Clement V, stood in their way. He did not, despite William’s suggestion, support the arrest. The king, knowing he could not yet forsake papal support, paraded 72 imprisoned Templars before Clement on June 29 and July 2 of 1308. The pope protested and even castigated William in particular for his in effect serving the crown of France, rather than Holy Church. But, in the end, Philip was victorious and the Templar order was dissolved.

Hence, we see how centralized “state” authority began to manifest Neither aristocrats nor churchmen stopped Philip; in fact, many of them, most notably William of Paris, colluded with him. He began to carve out some semblance of authority for himself and for himself alone. How would this nascent, dare I say “modern,” entity contend with the looming plague?

Not that well. Jews were often blamed for poisoning wells and causing the Black Death; this occurred to such an extent that Pope Clement VI had to condemn their persecution in both July and September of 1348. Philip IV had previously (and with William of Paris’ assistance) expelled the Jews and confiscated their property only the year before his venture against the Templars. They had been allowed to return but found themselves attacked and defamed. This should not surprise us: does the modern state not necessitate an enemy, something against whom its cohesion might be made real, made tangible?

Philip VI, king at the time of the initial outbreak, ordered prelates at the University of Paris to draft a book on disease, entitled Compendium de epidemia (Compendium on the Epidemic). This text spends many pages discussing the causality of diseases, attempting to apply cutting edge theories of pathogenesis to the plague; it, however, served mostly as royal gesture, a way of demonstrating concern, concern motivated both by real fear and by a need to uphold the coherence of the would-be state.

Such cohesion was, in its way, impossible. The Hundred Years War loomed, as did the near total collapse of French regal authority; its bureaucracy would not be revived in a substantial way until the reign of Louis XI (1461-1483). Louis was called “the prudent” and “the spiders”; his machinations, and most notably his reining in Burgundian power, would lay the groundwork for the “modern state” that was Early Modern France, that is, the Ancien Régime. But this was all far off—Philip IV’s efforts at centralization were premature; medical technology was too simple.

And so, it is literature (alongside what historical records we have) that gives us some glimpse of plague time in the middle ages. Suffering was great; one response to this suffering was, according to Giovanni Boccaccio, to entertain one another. Hence, his Decameron begins:

To take pity on people in distress is a human quality which every man and woman should possess, but it is especially requisite in those who have once needed comfort, and found it in others. I number myself as one of these, because if ever anyone required or appreciated comfort, or indeed derived pleasure therefrom, I was that person. (Boccaccio, Decameron, 1)

We should not forget that this strategy is that of the rich, of the literate and well-to-do—but a strategy it remains nonetheless. His characters quarantine themselves and seek distraction—and hope—in a variety of tales, tales that capture the full breadth of human emotion. For, in discussions of tragedy, pain, romance, and taboo, these people find the sense of belonging, the sense of community, with which Boccaccio opens his book. They, in other words, live lives of dissolution, of luxury, as a means of escape from the world—they laugh at it, they cry about, and thus they cope with it.

Jimmy the Peanut Farmer

This should sound familiar. We live in an age of divestment from the common good; neoliberalism—deny its existence if you must, the effects, by whatever name persist—sees austerity, sees the weakening of the state. Our simple political models remain invested in the Cold War: big states are Communist and bad. Freedom is the product of a small, limited government. Yes, freedom—the freedom to not wear a mask in public, the freedom to cough in someone’s face, the freedom to lack medical services in a time of crisis. Many know that Trump disbanded the CDC’s pandemic unit before the events of early 2020. But Ronald Reagan shuttered mental hospitals. Bill Clinton signed NAFTA, signaling the deindustrialization of the United States and the rising immiseration of the American worker. Jimmy Carter, of course, first began to decry the excesses of “big government”:

We need patience and good will, but we really need to realize that there is a limit to the role and the function of government. Government cannot solve our problems, it cannot set our goals, it cannot define our vision. Government cannot eliminate poverty or provide a bountiful economy or reduce inflation or save our cities or cure illiteracy or provide energy. And government cannot mandate goodness. Only a true partnership between government and the people can ever hope to reach these goals.

Those of us who govern can sometimes inspire, and we can identify needs and marshal resources, but we simply cannot be the managers of everything and everybody.

We here in Washington must move away from crisis management, and we must establish clear goals for the future, immediate and the distant future, which will let us work together and not in conflict. Never again should we neglect a growing crisis like the shortage of energy, where further delay will only lead to more harsh and painful solutions. (Carter, State of the Union Address)

President Carter was more prophetic than he knew: we have moved away from even the façade of crisis management. Now we cannot even imagine the management of crises.

Though Americans often trace their military overextension and divestment from the welfare state to the Reagan presidency, it began—if only nascently—under Carter. When asked about funding Afghan mujahideen to fight the Soviets, his national security adviser, Zbigniew Brezinski, reminisced: “What is more important in world history? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some agitated Moslems or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the cold war?” (“Brezinski Interview”) This short-sightedness in foreign affairs mirrors the administration’s domestic shortsightedness, leaving the US woefully underequipped to face any systemic shock. Even as the military budget grows, more of its functions are privatized, making for a force at-once bloated and lean. A cut here justified by a whitepaper there—Compendia de epidemia for a new age. Facts may proliferate, may be deployed as a supposed stopgap. But crises keep striking, with only a weak shell left to falter at management. The appearance of coherence must abide, but the limits of the paradigm cannot be questioned.

And that is the key: plague is a subspecies of crisis. Weakened states do not make for effective “crisis management”; in fact, they make for crises. Medieval French kings, even at the heights of their power, could do little but order research and find scapegoats. Popes tried to stop them, but to little avail. All this begins to sound a bit too familiar.

Are we not back at Winner and Waster? Our arguments are shaped by our material realities; we do not debate winning and wasting within feudalism, but instead proffer various choices within our capitalist framework. The Black Death would, surprisingly, lead to greater mobility and income for workers, even as the landlords and aristocrats did their best to maintain the old way of things. Good can, it seems, come of ill.

I do not mean, however, that we should assume it will: better wages are not worth half a country’s being dead. And no outcome is guaranteed. No, rather I hope to have suggested just how limited our capacities are, how our ability to respond mirrors, in its way, that of another historical time. Will we valorize weakened structures? Take advantage of them? Rebuild them? Destroy them? Or will we pass time telling stories, tucked away without laughter and our tears?

Chase Padusniak