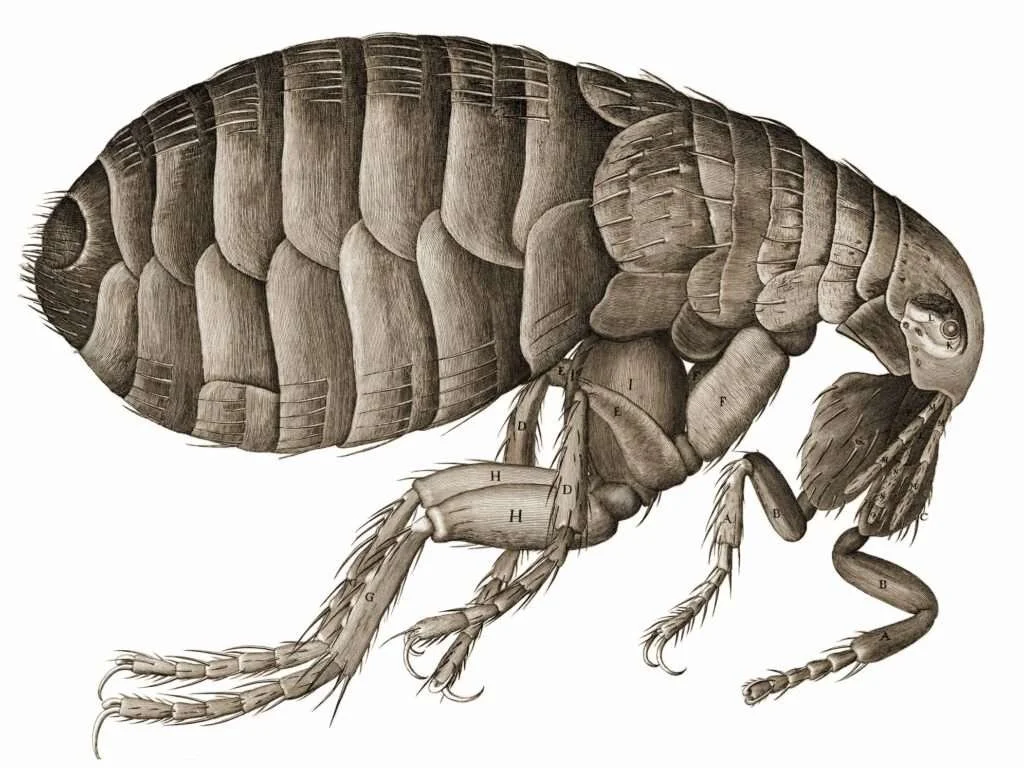

Pestilence

/Claims to the contrary notwithstanding, the scholastic notion of just price concerned market prices. Most histories of economic thought begin with Adam Smith, or at the most, with the ‘schools’ described by Smith, such as mercantilism. However, ever since the 1950s it has been well established among specialists that the first seeds of the modern supply-and-demand theory of value originated in scholastic just price teaching somewhere in the second half of the thirteenth century – most clearly expressed by a Franciscan, Peter John Olivi.[1]

Around that time, trade in Europe underwent development rapid enough to have merited the term ‘revolution’ with some scholars. In response to this fast urbanization, commercialization, commodification, and monetarization, just price doctrine developed towards a notion of market forces of supply and demand that were not the result of political design, but depended on factors too complex to be controlled. In any case, in a series of fascinating considerations of love and justice, just price was defined as competitive market price. It was not our version of competitive market price, yet there is no doubt that it was a competitive market price. Justice was defined in terms of free consent, and competition, it was thought, would protect buyers and sellers from economic coercion.

Then, however, the Black Death swept through Europe and decimated its population. The general tragedy apart, the following also happened which may be of interest in our current historical moment. Workers were literally scarce, and came in high demand. Across Europe, elites shortly came to fear that they were about to suffer significant loss if market forces were given free rein in relation to labor. Wages were often fixed at pre-pestilence levels and moreover, free movement of workers was commonly prohibited, often in a manner that verged on the irrational.[2] One might venture to speculate they were in part motivated by the governing parties’ fear in the face of the unknown, their felt loss of control as history seemed to take an entirely unforeseen direction.

There is no parallel between our times and that of the Medieval pestilence. For one, the corona pandemic is from a purely medical perspective nothing compared to the catastrophe of the Black Death. However, the history of how the market was conceived in a sort of self-equilibrating way, and then all of a sudden regulation was decided to be of essence, may be instructive. Presently, it is obvious that the political has decisively stepped onto the economic scene. Indeed, what has been revealed is that political authority was never absent from the purportedly self-balancing market. Furthermore, some have already observed that the pandemic functions as a kind of excuse to lever authoritarian forms of rule in different settings, also in the midst of liberal democracies, in the manner of ‘the state of exception'.

In brief, the present is a time when vigilance is of essence, and fear must be reined in. Neither strong nor (so-called) weak states will serve the masses whose productive forces may be capitalized on by means of market forces or centralized rule alike. Much may change, for better or for worse. We might want to rise to the occasion and make sure it is for the better.

Rosa

[1] See e.g. Odd Langholm, “Olivi to Hutcheson: Tracing an Early Tradition in Value Theory,” Journal of the History of Economic Thought 31, no. 2 (2009): 131–41, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1053837209090154; Joel Kaye, A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of a New Model of Equilibrium and Its Impact on Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Raymond de Roover, “Scholastic Economics: Survival and Lasting Influence from the Sixteenth Century to Adam Smith,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 69, no. 2 (1955): 161–90, https://doi.org/10.2307/1882146.

[2] See e.g. Samuel Cohn, “After the Black Death: Labour Legislation and Attitudes towards Labour in Late-Medieval Western Europe”, Economic History Review 60, no. 3 (2007): 457-85.