Empiricism and Ecstasy

/For Boris Gunjević

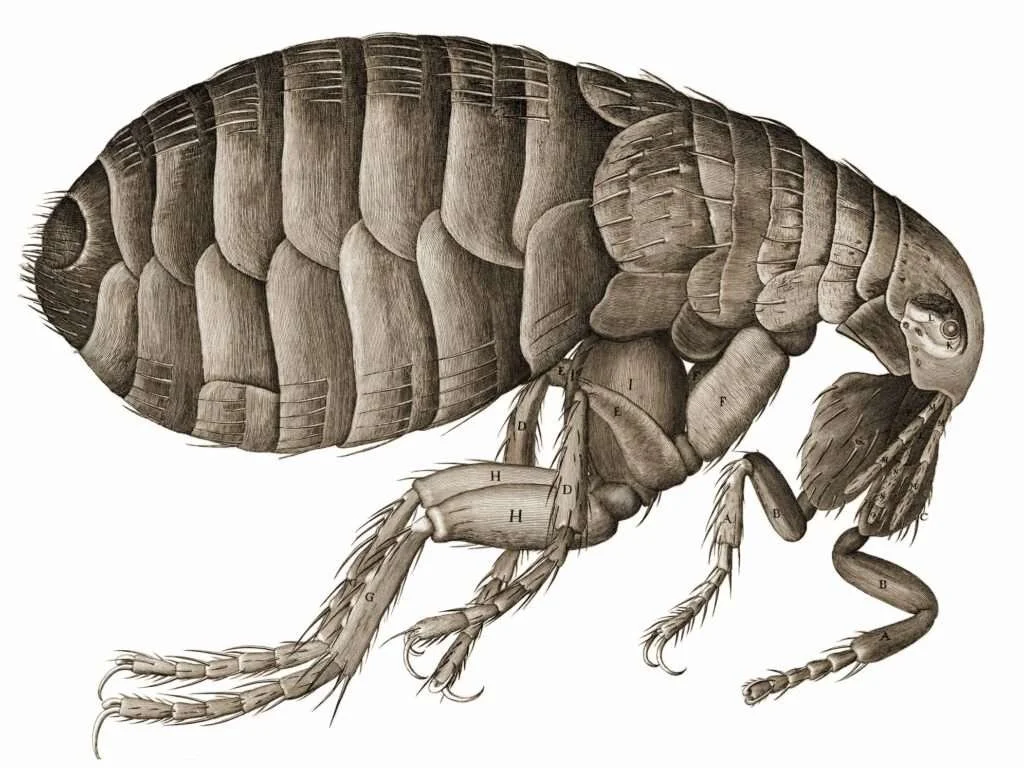

In the broadest terms, the method of empiricism must be sought in the procedures of mysticism. It is a question of direct experience, of distinguishing ideas about the self, God, the world, from the immediate apperception of what lies beyond the grasp of human reason. What can we really know, given that all we know, seemingly, is mediated by signs? Empirical “scepticism” is nothing but the dark night of the true believer. The empirical project comes to light only when we turn back to mysticism, for mysticism is not just one fantastical literature among many others. Mysticism – in the sense described so well by Michel de Certeau in his study of the seventeenth-century spirituals – assembles techniques of self-scrutiny into an “experimental science” that prepares the way for subsequent developments in philosophy, science and psychology.[1] One might at first want to say that this experimental science amounts to a preoccupation with inner and outer observation: this would explain the parallels, so remarkable, between the method of attention described in Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises and the method of observation in thinkers like Robert Boyle.[2] But this is only the superficial aspect of mysticism, its propaedeutic aspect. If one takes this aspect seriously, the rift between empiricism and religion on the one hand, and between mystics and orthodox institutions on the other, would evidently be in order: empiricism would then be the scientific equivalent of a spiritual Pelagianism or Stoicism, since the emphasis would then solely be on the human effort (procedure) to achieve clarity, and this would lead us to conclude that the experimental science in the end affirms rather than challenges the ideals of human reason it sets out to resist.

Augustin Lesage

The real purpose of an experimental science must be sought elsewhere. In Condillac’s Treatise on the Sensations (1754) an initial definition is reached according to which subjectivity emerges in a human being as its sensible faculties are increased. Without the senses, there is no self: the statue, which at first is able only to smell, cannot differentiate between itself and the perfume of the rose under its nose. But all sorts of enigmas spring up from this explanation, the most obvious being a curious and inexplicable “fundamental feeling” of spontaneous volition that seems, Condillac remarks in a pregnant footnote that invokes Leibniz in spirit if not by name, to precede even the senses.[3] As a result, when the statue, whose senses have been activated one by one over the course of the essay, is awakened to full consciousness and able to speak, what it declares, in its final breath, is the irreducibility of the self to the senses and thus to the very theory of the Treatise itself:

I see myself, I touch myself, I am conscious of myself, but I do not know what I am. If I believe myself sound, taste, colour, smell, I am no nearer the true knowledge of what I myself actually am.[4]

The purpose of empiricism then is not to explain the self by means of the senses, but, using observation of the senses as a propaedeutic technique, to contemplate the self in a state of ecstasy. This accounts for the perdurance, otherwise so inexplicable, of identity in Condillac’s analysis of the self: nowhere is the experience of identity denied; it is merely “the philosopher” whose “framing” of “language” is denied its explanatory suasion when articulating what is at stake in the experience of the self.[5] Empiricism is less a philosophical dissolution of the self than it is a dissolution of the constructions of the self by philosophers. Empiricism does not remove mystery but exposes it to view in a kind of apocalypse; it is a method for removing the carapaces of language, which, enveloping experience, make it inaccessible to immediate apperception.

In order to achieve this, Condillac makes the admission of language’s inadequacy the central feature of his thought. When language no longer suffices, one must either invent one’s own or defer to experience and to the eliciting of experience: one must show, not tell. In his later work, especially in the unfinished La Langue des calculs, Condillac will experiment with the former ambition, which we may describe as the aims of positive philosophy in contrast to the motives of an experimental science. Eventually Condillac’s invented language will lead to a new dogmatism in French thought, the “system” of Condillac as developed by Idéologues such as Antoine Destutt de Tracy and Charles Bonnet: a combination of plain style, analysis (“decomposition”) and materialist suppositions. But Condillac himself never appears satisfied nor entirely confident with his ambition, stated as early as the Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge, to “somehow make a new language for myself.”[6] Thus, the Treatise sees him showing rather than telling, and preferring the role of the spiritual director to the philosopher. From the very beginning of the Treatise, the reader is reminded to expect not so much an argument as an exercise. Or rather, they are advised that the effectiveness of the argument will rest less on its internal coherence and more on the degree to which the thought-experiment (the statue) is entered into:

I wish the reader to notice particularly that it is most important for him to put himself in imagination exactly in the place of the statue… He must enter into its life… I believe that the readers who put themselves exactly in its place, will have no difficulty in understanding this work; those who do not will meet with enormous difficulties.[7]

What stands between the reader and comprehension is not reason but imagination. How vividly, how deeply, can you imagine? This, the spiritual exercise of the Treatise, appears to stand in stark contrast to the dogmatism that will emerge from Condillac’s work after his death and hold sway over French thinking for several decades. In fact, the spiritual exercise of the Treatise contradicts nothing. On the contrary, the Treatise is but a different response to the same realisation that fuels any positive philosophy: the desire for a more immediate, more direct, expression of truth. Positive philosophy, with its ambitions to found language itself anew, is impossible without an initial intuition of language’s failure. At the same time, for this very reason positive philosophy imparts a false sense of hope regarding the supposed adequacies of its own language. In this sense, the Treatise is more precise because of its inability to name with any degree of precision. But the fact that it does name also makes it easy to confuse its reticence for a new dogmatism. After all, the Treatise quickly loses the plot of the spiritual exercise it sets out to be: in the end, it is a treatise, a long-winded attempt to describe and name the senses. The very fact that Condillac felt he needed to advise the reader of how to read the Treatise (that is to say, as a prompt to experience rather than as a proof) indicates that the text itself does not give accurate indication of this purpose. The experimental scientist who sets out to transcend the inadequacies of language finds himself, in the end, captive to its devices.

The charming admissions of personal failure that interrupt the text of the Treatise by Condillac follow from this. He has not, he claims, “always succeeded” in putting himself in the place of the statue.[8] The author is not a master: perhaps you, the reader, will succeed better. One might express it in the following manner: let us not set out to prove the existence of this or that phenomenon (God, the self, the world) but rather to prompt an experience, a radical immediacy with the phenomenon in question. It is a quest for evidence, to be sure, but evidence of things that lie beyond the grasp of reason and the senses: what Wittgenstein called Gewissheit, a certainty that runs deeper than reflection and to which reason is an afterthought. It is contemplation, the “seeing” rather than the comprehension of truth. The question is not, “do you judge this argument to be valid?” but “did it work for you, and how well did it work?”:

It should be understood that the uncertainty or even falsity of some our conjectures need be no prejudice to the basis of this work. When I observe this statue it is not so much to be assured of what is taking place in it, as to discover what is taking place in ourselves. I may be wrong in attributing to it operations which it is yet incapable of, but such errors are of little consequence if they put the reader in the state of observing how these operations take place in himself.[9]

Empiricism asks us to consider whether there is not a kind of knowing that is more certain despite and not because of the evidence of the senses. In this way, empiricism constructs the method of mysticism or the experimental science according to which discourse is not used to claim truth but rather to facilitate the experience of truth in the life of the reader.

At the same time, the fact that empiricism no less than mysticism frequently takes umbrage at the traditional formulations of theology matters, because by and large the theology of the academy has forgotten its dependency on the mystics’ procedures, their “techniques of ecstasy,” leaving these instead to be studied by anthropologists and historians.[10] It is no coincidence that those religious writers for whom immediate apperception was of the utmost importance were also those most frequently accused of heresy: mystics, in the delight they show toward the data of immediate experience and the glory of the senses, are the most empirical of theologians, and for this reason the most despised by theology itself. If empiricism reclaims religion, it does so on the same terms as mysticism, becoming “an instrument for unveiling, within religion itself, a truth that would first be formulated in the mode of a margin inexpressible in relation to orthodox texts and institutions… The study of mysticism thus makes a nonreligious exegesis of religion possible.”[11]

Simone Kotva

[1] Michel de Certeau, The Mystic Fable. Vol. 1: The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, trans. Michael B. Smith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 7.

[2] David Marno, “Easy Attention: Ignatius of Loyola and Robert Boyle,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 44, no. 1 (2014): 135-161.

[3] Condillac, Treatise on the Sensations, trans. Gerladine Carr (London: Favil Press, 1930), p. 8, n. 1.; cf. p. 75. See Jeremy Dunham, “Habits of Mind: A Brand New Condillac,” Journal of Modern Philosophy 1, no.1 (2019).

[4] Condillac, Treatise, p. 236.

[5] Condillac, Treatise, p. 222.

[6] Condillac, Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge, trans. Hans Aarsleff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 19.

[7] Condillac, Treatise, xxxvii; the advice is repeated at p. 57.

[8] Condillac, Treatise, 57.

[9] Condillac, Treatise, 57.

[10] Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, trans. W. Trask (Princeton: Bollingen, 1964).

[11] Michel de Certeau, “Mysticism,” trans. Marsanne Brammer, Diacritics 22, no. 2 (1992): 11-25 (p. 24).