Unlearning Attention: On the Failures of Environmentalism

/For Jack Belloli

There are many reasons why environmentalism fails and continues to fail despite the escalating planetary emergency. Many of these reasons are internal to environmentalism itself and are connected to the ideals shaping it – as such, they are tricky to identify, much less to examine and act upon, as Bruno Latour, Timothy Morton, Isabelle Stengers and others have shown in their recent work. The task is compounded further by the fact that so much of environmentalism has come to take on the quality of an ersatz religion, with the tenets of ecological ethics especially held up as unquestionably just and true.

Take, for instance, the idea that we need to “pay more attention” to our surroundings, that we suffer today from an attention-deficit disorder that is also a nature-deficit disorder (as popularised by Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder, 2005). At first blush this seems a reasonable assumption – indeed, Stengers in particular invokes the practice, arguing – in Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism (Eng. trans. 2015), and other places – that we have lost the “art” of “paying attention.”

But attention has many faces and not all of them kind.

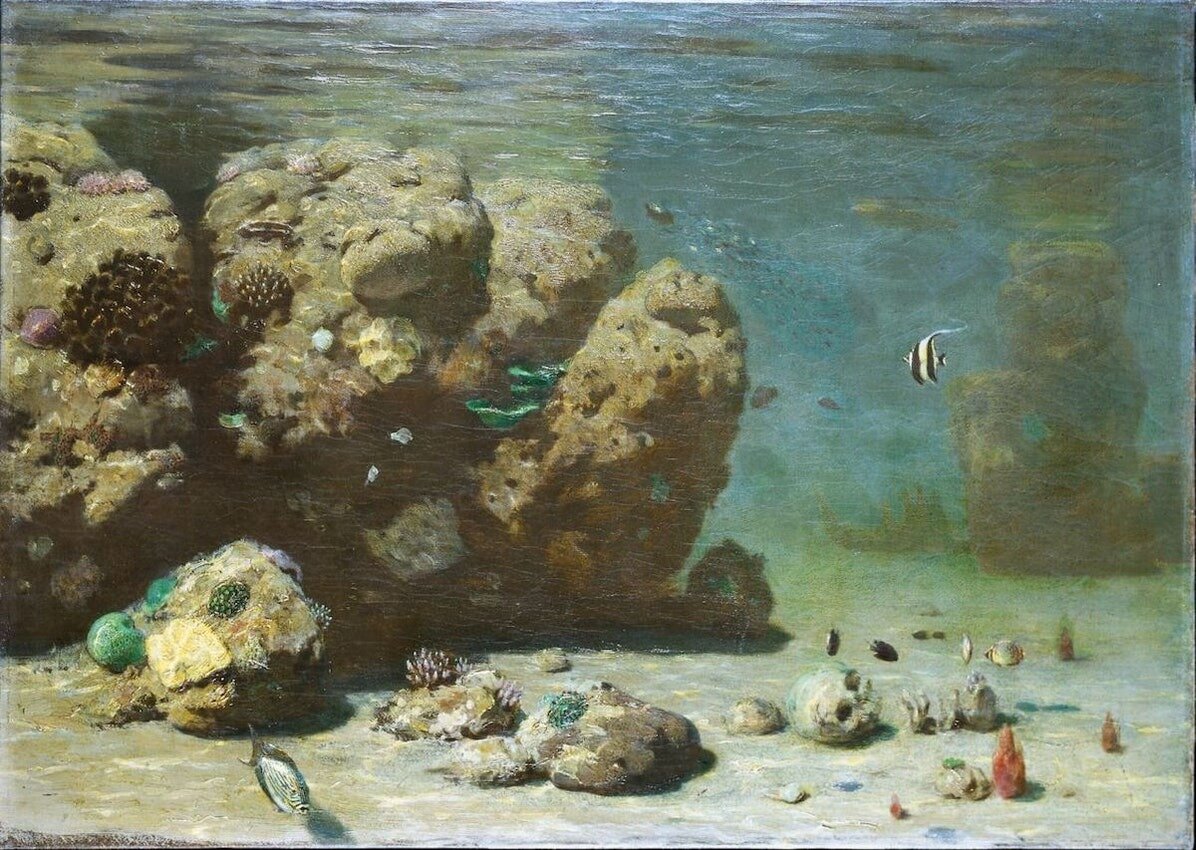

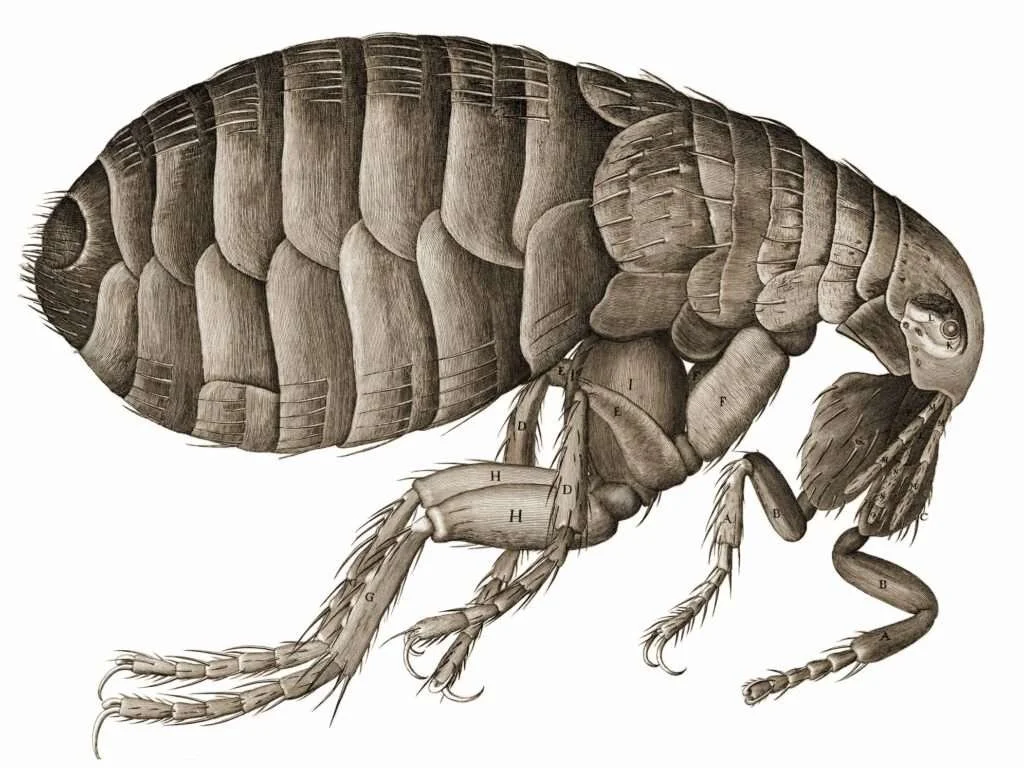

“Attention” is the ability (particularly well-developed in hominids) to focus the mind at will on a few things to the exclusion of others. Above all, attention is what allows us to be fascinated and take an “interest” in things and ideas that are not strictly necessary for survival. That interest results in the innocuous heaps of pretty shells and tumbled glass that adorn childhood bedrooms; but it also, and less innocently, has been responsible for the practice of filling glass cabinets with stuffed organisms and looted artefacts “collected,” at great cost to original habitats and surroundings. Thanks to scholars like Carolyn Merchant and Kathryn Yusoff, the key role played by early iterations of modern science in paving the way for the environmental crisis is well known; as is the role played by colonialism in facilitating the exploitation of natural and cultural resources without which the Anthropocene would have been mostly unthinkable (the key arguments are well-presented in Simon L. Lewis and Mark. A. Maslin, The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, 2018).

Make no mistake about it: in the history of recent, industrialised and urbanised, civilisation, it is an excess of attention – not a lack of it – which has played a huge (and hugely under-acknowledged) role in overheating this planet. A host of vital feelings and crucial cares – compassion, decency, companionship – should have tugged at attention and distracted it from its foci, but they did not; in this instance, the fact that creatures and persons were literally dying as a result of the “attentions” paid them seemed of little consequence.

If this is so, what then do writers like Stengers mean when they say that we need to relearn the art of paying attention?

There is a wonderful passage in one of Isabelle Stengers’ recent essays, Another Science is Possible (Eng. trans. 2018), where she describes the predicament I have been sketching above, but instead of making a distinction between attention and distraction she writes about two modes of attention: fast and slow. Fast attention corresponds to what I have just described as the effect of focussing on one thing to the exclusion of others. Stengers compares it to the attitude of a mobilised army of men at war: whatever villages and fields are ravaged as a result of their progress makes no difference to the army’s ideal of “progress.” There is an obvious analogue here to be drawn with capitalism. Capitalism has been called the economy of attention par excellence, focussing all resources on single goals to the exclusion of a multiplicity of interconnected long-term concerns. Thinking with this comparison, Stengers argues that what we need to do now is not to stop paying attention but to “demobilise” our efforts and “slow down.” Crucially – and this is where her description of “slow” attention overlaps with distraction – for Stengers slowness allows attention to be open and receptive: surprised by “what may lurk,” an ability that Stengers thinks is at the heart of what environmentalism should be all about (see Stengers’ interview with Martin Savransky, “Relearning the Art of Paying Attention,” SubStance, 40/1 (2018): 130-145).

These are subtle points, though, and without the shift in modality described by Stengers – the shift from attention being something I do (effort) to becoming something I am (effortless disposition) – the truism of attention is neither self-evidently true nor inherently just; quite the opposite. The horrific carbon footprint accrued by people travelling half-way across the globe to gaze enraptured at landscapes and creatures or enjoy leisurely recreation in untouched (sic) wilderness is the most obvious example of how attention that is fixed on one thing to the exclusion of others leads to injustice – even, not to say especially, when such activities are undertaken in the name of environmental concerns. To take a local example: in the country where I grew up, Sweden, environmental literacy is extremely high and yet the country is among the top nations consuming less sustainably. A recent poll showed that what Swedes save by switching to “green” sources of energy they typically tend to spend on tourism and recreation in remote beauty spots (an even more extreme case is Norway, where the building of holiday cottages in undisturbed areas threatens the very biomes of the ecosystems celebrated by holiday-makers.) It is a good example of environmental literacy and “attention” to place ironically contributing directly to its exploitation.

For this reason, and although I agree entirely with the “slow” modality of awareness described by Stengers, I wonder if calling it attention has enough of the shock about it really to matter – for the mattering of the planet.

As E. O. Wilson has argued, the best – and perhaps the only realistic – response to ecosystem degradation is to remove urbanised humans from the equation, as far as possible. The so-called “half earth” theory forecasts a future where most humans live in cities and the countryside is restricted to those who have actual business there: farmers, animals, and so forth (Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, 2017). The fact is that the environment can look after itself and does not need input from us in order to repair itself adequately. In other words, it does not need human “attention,” at least not the kind of attention it is most often given by the urbanised person who buys a “green” house in a village in order to escape the city, but then proceeds to devastate the environment through their daily commute to the office. Of course, the idea of living in a city without ever being able to “escape” to the countryside sounds monstrous – but that has more to do with prevailing attitudes to cities than it has to do with urban environments as such. As Kim Stanley Robinson remarks, when we find ourselves unable to indulge our attention in the countryside as an “escape” we may become, finally, able to be distracted sufficiently by the cares of our immediate environments: the well-being of our neighbours, the well-being of neighbouring biomes; the state of the sewers, etc. As long as our attention is focussed elsewhere than on these immediate surroundings, whatever efforts we put into protecting remote wetlands and red-listed species – as important as such concerns are – will fail to make an impact on the global situation. Indeed, they will lead to counterproductive rebound effects (Robinson, “Empty Half the Earth of Its Humans: It’s the Only Way to Save the Planet,” Guardian 20 March 2018).

Even so, I find myself returning continually to the concept of “paying attention.” There is something here to which I am drawn. Perhaps it is because the effect of attention on the nervous system mimics the effect of certain enhancing drugs and can supress awareness of vital bodily functions. This is a common sensation among writers. While attention is high one feels physically high: less aware of the body, less able to be distracted by bodily factors such as temperature, hunger and pain. That ability to block out vital functions can be useful – it is how the majority of this post was written in a cold room with no heating – but it can also be harmful. If the body is coming to serious harm as a result of attention – if it dies, even – arguably the activity is not particularly beneficial. That Romanticism has taught us to admire such deaths compounds the problem. We secretly desire to go out on a high. But when “the body” is the world in all its variegated multifarious life, and mass extinction its “death,” we must ask ourselves whether this particular high is worth the price we are paying for it.

Perhaps it is time, then, that we learnt not the art of attention but the art of distraction.

Simone Kotva