A Necromantic Critique of Reason

/For Christian Coppa

What is Continental philosophy? It can be distinguished from analytic styles of philosophising in that it doesn’t reference concepts in the abstract but discovers the concept embodied in the thinking of another person. Most often, that person is deceased; in every case, they are mortal. Continental philosophy writes itself therefore as an encounter with the dead; it is ‘historical’ and concerned with the ‘history of philosophy’ in so far as it thinks by thinking with others who have thought before. It is through this thinking-with the dead that the concept is embodied; the writing of the living philosopher becomes inseparable from the thoughts of the dead. It is a haunting, in that the text of the dead philosopher will begin to dog the words of the living in uncanny ways, inserting itself into the syntax of the living through quotations, paraphrases and jargon that haunt the words of the living. But it is also an evocation, in that the dead are thereby called forth (ex-vocare) by the living to perform functions and to serve purposes that were not their own in life. While the living speak by repeating the words of the dead, their repetition is not identical.

Is this not what Gilles Deleuze meant when he spoke of philosophy as an ‘immaculate conception’? ‘I saw myself as taking an author from behind and giving him [sic] a child that would be his own offspring, yet monstrous…because it resulted from all sorts of shifting, slipping, dislocations and hidden emissions…’ [1]

But the relation between the living philosopher and the dead is not only one of reciprocal violation – of the living by the dead (haunting), or of the dead by the living (evocation). Deleuze’s comparison to the immaculate conception of Mary, with its implication of total surrender is perhaps misleading. In truth the relationship is more akin to what the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro – himself in dialogue with the dead, with Deleuze – calls ‘negotiation’ [2]. Total surrender of the will has very little to do with it. An expert in necromancy (‘shaman’) is able to interact with ancestral spirits not because they are imposing and powerful individuals but because they know how to perceive the dead. This means that they know how to communicate effectively with the dead; they are the one who can ‘figure out’ what the dead need in order to feel at rest, or which spirits are in need of working more closely with the living, and which may be called upon to help with present emergencies.

The dead are not puppets waiting to be animated by the living, nor is necromancy the art of begetting monsters by corpses. Necromancy is the art of listening to monsters – in so far as the dead appear uncanny and monstrous to the living – and of learning with monsters. This is why Castro thinks of ‘the shaman’ as a critic of metaphysics: the spirit-expert’s ability to listen and be open to the spirits with which they interact demonstrates that crucial ability to be surprised without which genuine inspiration and discovery is impossible. In order to negotiate successfully, the necromancer treats each dead as a person. Never mind the monstrous appearance of the dead; it is their ‘personal story’ that is at stake.

Successful necromancy is above all a people skill. In order to work with the dead successfully the necromancer can’t be overcome by fear, but pity is also an impediment. The necromancer needs to be interested in this spirit not as a frightful monster but as a person, without excessive feelings clouding their judgement. A skilled necromancer knows when spirits are being troublesome but they do not assume an evil intent, or a good one. First, they listen, determining what the dead need and how they can be helped to get what they need.

Necromancy is a critique of reason. It is not superstition, but nor is it an ‘alternative’ worldview that exists in isolation from ‘Western’ approaches. Necromancy appears every time the reading of dead authors is ‘close’. It is to the degree that a student disregards what commentators have said ‘about’ the text and grapples instead ‘with’ the words of the dead person that Alain, in his memoires, argues that an interpretation in philosophy is ‘true’ [3]. The reading of a dead person’s text then has the possibility of becoming a genuine encounter. Commentary, by contrast, provides a buffer that prohibits direct engagement with the dead author’s text, the voice of which is thereby fenced in by so many caveats. Simone Weil, Alain’s most famous pupil, practiced something similar when she decided to read the Pythagorean fragments as if two thousand years of scholarship did not exist: ‘today the depths of Pythagorean thought cannot be perceived except by using a sort of intuition…’. To do philosophy one must ‘intuit’, that is, speak directly to the dead author’s text [4]. It is the opposite of commentary, of summary.

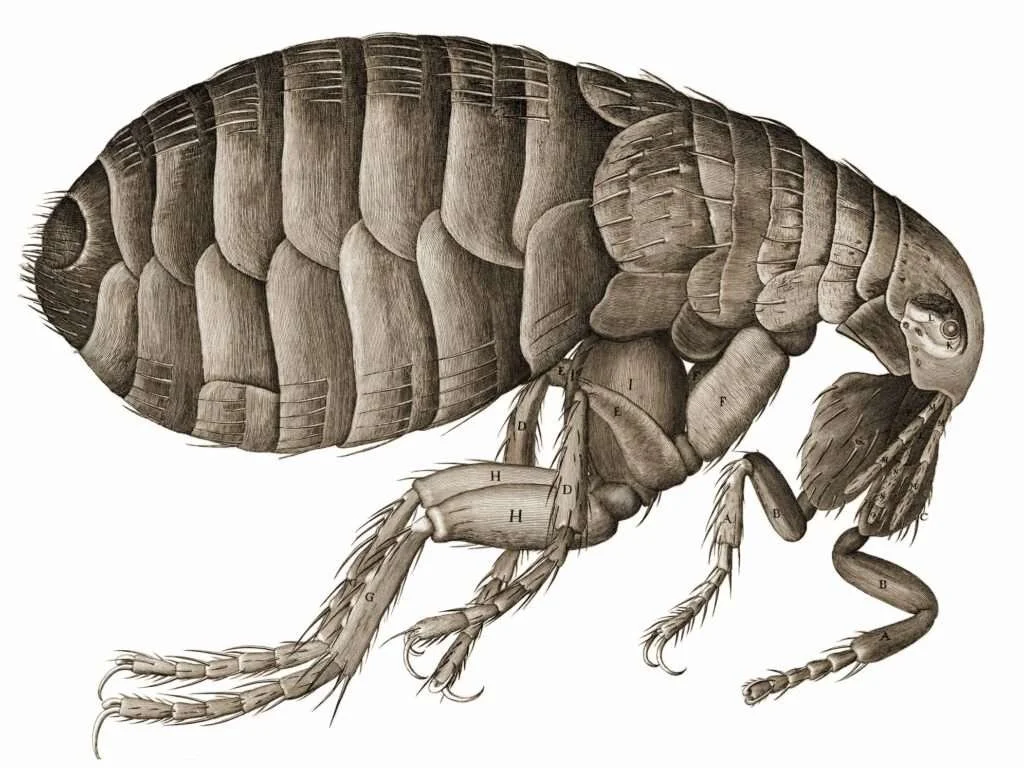

What is necromancy? An art of listening. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough is the best example of this art. The magical practices described and ridiculed by Frazer are considered here for their own sake without assuming the explanations of Frazer. ‘Even the idea of trying to explain the practices…seems to me wrong-headed’. Historical explanation is lazy. Frazer’s explanation of magic – that it is a primitive attempt at science – makes it easy to judge magic as backward and superstitious, without paying it any further attention. The explanation has done the listening for you; it has made any fresh attempt to ‘hear’ the evidence impossible. Frazer treats magic as a museum artefact which it behoves the viewer to interpret in a certain way. Frazer’s explanation is the glass case from which the viewer can safely engage the object without awkwardness. Wittgenstein by contrast treats ‘magic’ as a person. He does not presume to understand magic; he allows himself simply to ‘be impressed’ with it (‘does an “explanation” make it less impressive?’). Explanations of magic fail, he writes, not because they are illogical but because they do not make the practices themselves less interesting. Explanation, not magic, is thus ‘the stupid superstition of our time’. In other words, by resisting the lure of the explanation Wittgenstein is attentive to what lies outside the horizon imposed by the explanation. He listens, and while listening, finds that no explanation is sufficient to fathom this thing… If we are to begin to interact with it, ‘we must plough over the whole of language’, assuming nothing and leaving the mind as disturbed as newly-turned earth [5].

But we should not be afraid to be on our guard when the dead appear. The spirits of the past do not have our best interests at heart, or not necessarily. The expert spirit-worker described by Castro makes acquaintances in the spirit world; they do not make friends or lovers. The necromancer does not need to ‘like’ the dead, nor be ‘on their side’. In fact, it is considered dangerous to the health of the spirit-worker if they were to attach themselves too intimately to the dead. Necromancy is not full possession. At the same time, listening to the dead is impossible unless the spirit-worker leaves themselves open and vulnerable. For this reason controlled or voluntary possession is often a necromancer’s special skill. In order to listen well to the dead, the spirit-worker must be in a position where full possession could happen. It is then a question of letting the other in while pulling back from full possession. The philosopher who works with the dead is very much engaging these techniques, whether they are conscious of it or no. It is an experience halfway between control and abandon. The philosophy called Continental is always voluntary possession by the dead.

But why this need to qualify the term? In truth it is philosophy – neither this nor that style of philosophy – which, as a way of life, is nothing but necromancy. For there are no ideas in the abstract which are separable from bodies, no immortal truth that was not first spoken to the world through mortal lips. Every critique of reason is a necromantic critique; it knows the mortality of thought but it also insists on the irreducibility of thought to a single mortality – tothis philosopher, to me. When philosophy begins working with the dead (as opposed merely to summoning them willy-nilly) it discovers thought to be entangled in a history of past lives (of past philosophers and their thoughts) and so it finds itself acknowledging the limits of what can be thought in one lifetime. As a result, it becomes imperative to listen to others. What we call necromancy’s critique of reason is not a matter of subordinating the living to the dead but a task of levelling the playing field and acknowledging the co-constituted nature not only of ‘life’ but of thought.

Simone Kotva

Notes

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism, trans. H. Tomlinson and B. Habberjam (New York: Zone Books, 1991), p. 6.

[2] Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, ed. and trans. Peter Skafish (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[3] Alain (Émile Chartier), Les arts et les dieux (Paris: Gallimard, 1958), p. 27

[4] Simone Weil, ‘The Pythagorean Doctrine’ in Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks, trans. Elisabeth Chase Geissbuhle (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1957), p. 153.

[5] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough, trans. A. C. Miles and rev. Rush Rhees (Bishopstone: Brynmill, 1979), pp. 1e, 6e, 7e.