Retreat from the state zoology: A conversation with Camila Ramírez Lobón

/This interview by Gerardo Muñoz with the Cuban Artist Camila Ramírez Lobón (1995-) was originally done for Ficción de la Razón in December 2020 a month after the so-called “Revolution of the applause”; an unprecedented gathering of the youngest generation of Cuban visual artists and journalists (up to 500 people) in the courtyard of the Ministry of Culture in Havana in defence of the jailed Cuban rapper Denis Solis and others belonging to Movimiento San Isidro – a network of artists, journalists, and musicians who protest against state censorship and struggle for free speech.

Although the discontent had been brewing for months in the wake of the 349 & 370 executive decrees that place limits on autonomous artistic creation (both in terms of content and circulation of the artwork), the seating was an unparalleled event for multiple reasons. First, it was an initiative coordinated by the youngest members of the visual arts generation and not by professional “political dissidents”. Secondly, the demand of the artists did not revolve around mere recognition of their talents and artistic capital by the institution; rather it seized the opportunity to request a transformation of the conditions of life against the absolutism of the state. Thirdly, the officials of the Ministry had to give in and accept conditions for dialogue (a dialogue that now, after an altercation this past 27 of January seems no longer possible, as now the top officials of the institution call the protesters “provocateurs”) with three representatives of the movement.

One of these was the young visual artist Camila Lobón – a graduate of the Institute of the Arts (ISA) at the top of her class, and whose work has been featured in national and international exhibitions – who was arrested January 27 together with Celia Gonzaléz when Camila was scheduled to have a meeting with Vice Minister Fernando Rojas. They were stripped naked and their genitals searched since the police bizarrely wanted to make sure that they didn’t hide any recording devices. They were later released but the crackdown was a clear sign of the anxiety among the governing classes for a new unruly generation of dissidents that seem to upset many presuppositions of politics and dissident.

In fact, Lobón’s has made clear that for her generation the main question is to “affirm life” against the omnipresent state control over any deviation and dissent of citizens. Although the 27N “revolution of the applauses” cannot be called a revolt in the sense of the Chilean October of 2019, it does bring to the table a new energy, where the protagonists are very young women artists whose vital voice against the official feeble narrative of the state has intensified in the last two years or so. Since early December, Camila Lobón lives under police watch (a regular police car can be seen on her block), without ever having committed any crime or any formal legal case brought on her behalf. This is another substantial difference of the new generation of artists: where in the past others have left the island, this time they are resolute in following the rhythm of a coming transformation.

Camila Ramírez Lobón

The youngest generation of Cuban contemporary visual artists no longer believes in historical development and its apparatuses of culture. In fact, for this new generation what matters is to find a way out of culture and a route of the undercommons. For the new spirit of the youth (artists born between 1985 and 1994) what is at stake is a new economy of desire that pushes against the confinement of state institutionalization. This is why the central gesture of their artistic practices is a transgression of the rules and idols of the socialist state. Hence, their creations become a strategy to contest the depredatory game of state subjection into the abstract ideals of “sacrifice” and “progress”. The visual work of the young Camila Ramírez Lobón (Camagüey, 1995), in particular, is representative of this generation of artists. Retracting her work from the conventional moulds of the late Avant-Garde and its forms, Lobón's work destroys the apparatus of "vanguard art" as compensatory for the ruin of the socialist philosophy of history. In fact, her profane drawings and storytelling questions the cultural monuments and grand iconography proper to the “total work of art” of a revolutionary society, which can no longer orient the life of the youth [1]. In the wake of the ruins of the total artwork, the Cuban state has intensified its moral discourses, administrative decrees (in particular decrees 349 and 370 that seek to “regulate” norms for artistic creation in the context of the new global markets), and local level policing of the mobility of young artists that have created new autonomous spaces and publishers to circumvent the centralization of the Ministry of Culture. This past 27th of November a couple of dozens of Cuban contemporary artists stormed the entrance of the Ministry of Culture with no other intentions than to destitute their monopoly on creation and freedom of speech. The gathering had no clear political demands nor requested “official” recognition by the Ministry; rather its “gesture” consisted in putting into crisis the logistics of cultural mediation between the state and its cultural officials. Many of them spoke about a new form of “experience”, or, in the words of Camila Lobón, a new “desire for dissensus” that wants to poke holes in the texture of a total state’s production of fictions about well-being and sacrifice. It is telling that this new experiential eruption has emerged from within the community of the visual arts (recalling the “Escena de la Avanzada” in post-dictatorial Chile in the 1990s), confirming that the tonality of the youth condenses an energy against all absolutisms of reality and domestication. This “experiential” releasement is the point of departure of a new form of socialization that has begun to take off. As Chilean political philosopher Rodrigo Karmy has stated recently: fundamentally, the Cuban Revolution is to be understood as the other pole of the governmental apparatus of the Latin American civilization state form. In other words, the total social state and the neoliberal market have been the two laboratories for the enactment of historical production. This new gesture in art indicates a latency that seeks to break free from this historical prison (rooted in the “people”, the “state”, or “transculturation”). But we have the opportunity to exchange a few of these ideas with Camila Lobón from Havana, with whom I recently talked to about the events of 27N storm of the Ministry and her visual work.

Camila, I think I would like to begin by proposing to you the question of a generational break. It seems to me that the Cuban Avant-Garde of the 1980s (Arte Calle, performance, etc.) still had hopes in the vanguard to transform the institutions of the State from within. After all, the goal of the artistic avant-garde was to dispute the leading role of the political vanguard (the Party). On the contrary, your generation seems to move away from this position, leaning towards something more vital, experiential, and interested in fragments of visualizing the world and its relations. In other words, it seems to me that your work points to an incommensurable abyss between life and politics of the state. Do you see it also in these terms?

Camila Lobón: Yes, I like this way of putting it very much, although I will confess that I tend to look back with nostalgia to the artistic production of the 1980s, and it's capacity to intervene in the public space (against the very notion of the ‘public’), probing the limits of what is permissible. I think that we can still use their gesture of trying to liberate artists from the burden of the “historical process” and everything that it entails. I look up to the 80s because I see honesty – a sort of divine innocence – that was literally destroyed. At the same time, of course, there are important differences between the artists who worked in the 80s and us. We have grown with new experiences in a world where the so-called global art market has been more present in our realities, which has internally enough allowed for the birth of new independent and autonomous projects. Today we have autonomous projects that literally delude the borders between creation and society. This generation – my generation – understands the state with cynicism, because it contests the limits of the rights granted to artists. I tend to think that my generation is interested in thinking through the problem of rights and not so much of the work of artistic radicalism, so trendy in the global hubs of contemporary art. I think that Ángel Delgado’s carceral experience in the 1980s (eight months of prison for shitting on the official newspaper of the Communist Party, Granma) connects to what has happened to Luis Manuel Alcántara, who has been arrested for his artistic performances. This is an important parallel. This generation gains momentum in its capacities to retrace new actions, in my view.

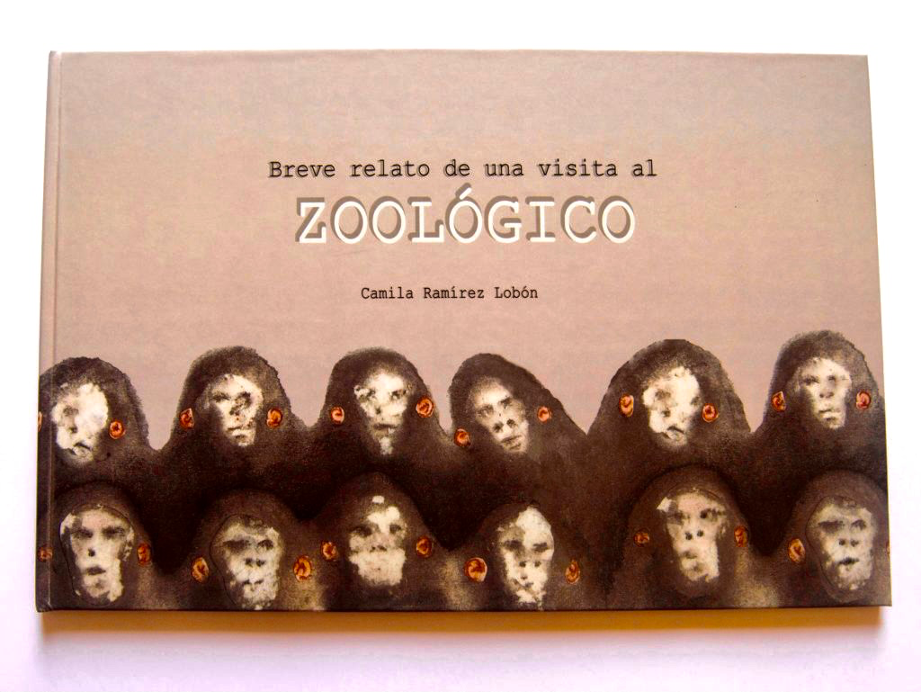

I like very much how you approach problems from a spatial or territorial gaze, as if for the artist of your generation is solely interested in generating a vital energy against the force of state neutralization. I think immediately of your book-object Breve relato de una visita al Zoológico (A Brief Story about a Visit to the Zoo, 2017), which allegorizes the history of the socialist state from the point of view of a young boy who visits a zoo. Here we no longer have the melancholic gaze of the city in ruins, which was so common in the fiction and visual arts of the 90s; rather there is a de-fictionalization process of the gaze that understands the state as a site of captivity. When you went into the Ministry of Culture, you also claimed against the total convergence between state and society, that is a retreat from the zoological condition. Could you elaborate a Little more about what took place that day of November in Havana?

Camila Lobón: Yes, a representative of the Ministry told me that the streets only belong to the revolutionaries. She was the first one who saw us enter as we waited for the vice-president of the Ministry, Fernando Rojas. I immediately told them that the streets belonged to no one, and that only from the position of power could one negate the right to the public assembly to the regular everyday people. This is simply a crime. The public space is a condition granted to me as jus soli, that is, just from the fact having been born in Cuba. I think that the violence of the state against the 27-N protest is first and foremost a reaction to this new desire for dissensus. This desire is above politics, which demands a “specific type of subjects (masculine too)”. I think this is something that will only intensify, since we have gained a lot in terms of autonomous space against the state. Today the state can only stigmatize and paralyze life.

When you speak about new autonomy I cannot but think of the proliferation and fragmentation of spaces in the social sphere. The autonomous becomes a way to escape the arbitrary function of the state over reality. I think this speaks of the spike of governmental decrees that seek to regulate what is permitted and what is not. In a way, this is what I am interested in your books: life in the form of the total state becomes a zoology of human life. In this sense it is curious that even a revolutionary state like the Cuban State of 1959, which was crafted institutionally in 1971 (“Proceso de institucionalización”) was incapable of attending to the crisis of the human community (Gemeinwesen) in relation to its socialization. Hence, we can argue that while neoliberalism absolutized the economy vis-à-vis the death-drive of subjectivity; the socialist state liquidates community form reducing it to mere biological survival. This is the story of the last thirty or so years since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the entry into the so-called “Special Period in Times of Peace” of the Cuban economy. Now, I find it very beautiful that your books are made as if they are meant for kids, although they are not infantile literature. Of course, we know that perhaps infancy is not a biological stage of the human but a process that runs through human life. This is a desire to live, and to live with others. Here I am thinking of the importance of “partying” (fiesta) for your generation, as a sort of clandestine form of life where new encounters take place. An Argentine friend speaks of the party as a life-affirming practice in the apocalypse [2]. In other words: the party is another way of freeing existence from the fiction of the zoology; a Jurassic Park in which obedience is the central fiction, as some have suggested [3]. Your books and drawings are a way to prepare an exit from the zoo; at least, to imagine it. But I would like to get your take on the relation between partying and the life of the youth…

Camila Lobón: Partying, yes, in fact, if you hear a little aphonic it is because just a few days ago we had a party after weeks of being confined and watched by the state police. Indeed, I think that in the context of the total state partying, or the joy of life becomes a sort of intuitive resistance. In other words, it is a way of not losing the desire for happiness. We defend each other in the party zone. The party escapes reality in the face of oppression. In the first place, the party is a space of community and self-defence. On the other hand, the party facilitates a communication for a potential transformation, and this is why the party is always the enemy of the state. The total state seeks the mere survival of life and the privation of the soul; therefore, the zoology metaphor to me speaks to this: a form of captivity that generates irreversible anthropological damage. Although I did not make these books for children, those children that have read it have understood everything. These kids have grasped the message without any sort of explicit political discourse.

Notes

1. Boris Groys. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (Princeton U Press, 1992).

2. Gerardo Muñoz. "Undomesticated life: A Conversation with Diego Valeriano", Tillfällighetsskrivande 2020: https://www.tillfallighet.org/tillfallighetsskrivande/undomesticated-life-a-conversation-with-diego-valeriano

3. “ But the event in Jurassic Park, the one that precipitates everything, is a dysfunction, a sabotage. It is the disconnection of the electric fence. Usually, this alone is the guarantee that dinos lead a policed existence that does not encroach on "the freedom of others." Once the electric fence is turned off, it's obvious what's going on. It's as big as a house: that's not what dinosaurs are made for. So that we can look at them from the outside. Then the sense of the island appears. There are not dinosaurs on one side, humans on the other. At the moment when the dinosaurs no longer recognize the fence, all the civilized division becomes blurred. Prison existence is first of all due to the functioning of the fence.” See “Éléments de décivilisation (partie 3)", Lundi Matin, 2019 : https://lundi.am/Elements-de-decivilisation-Partie-3

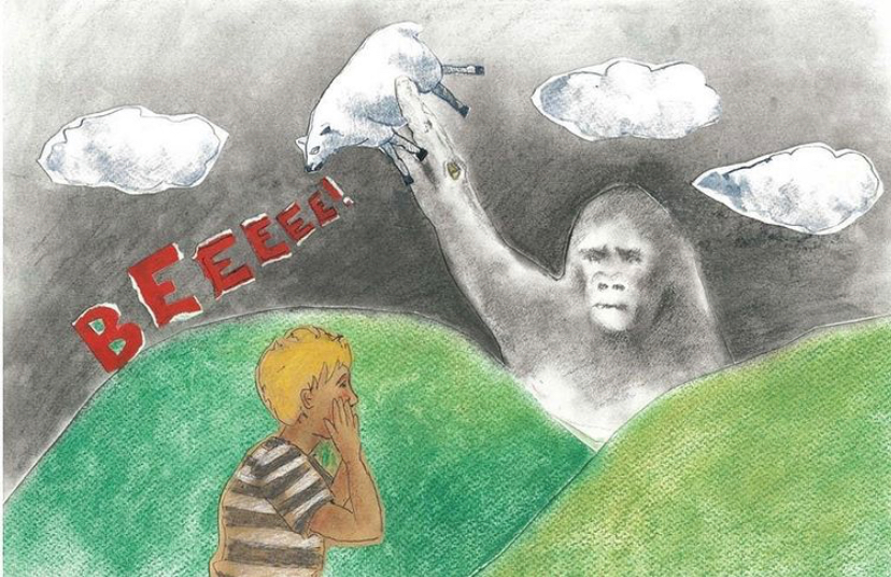

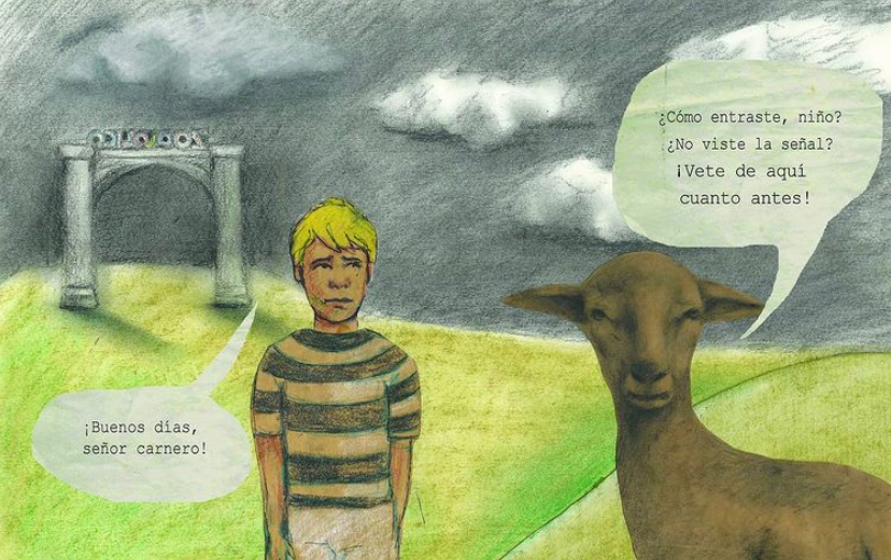

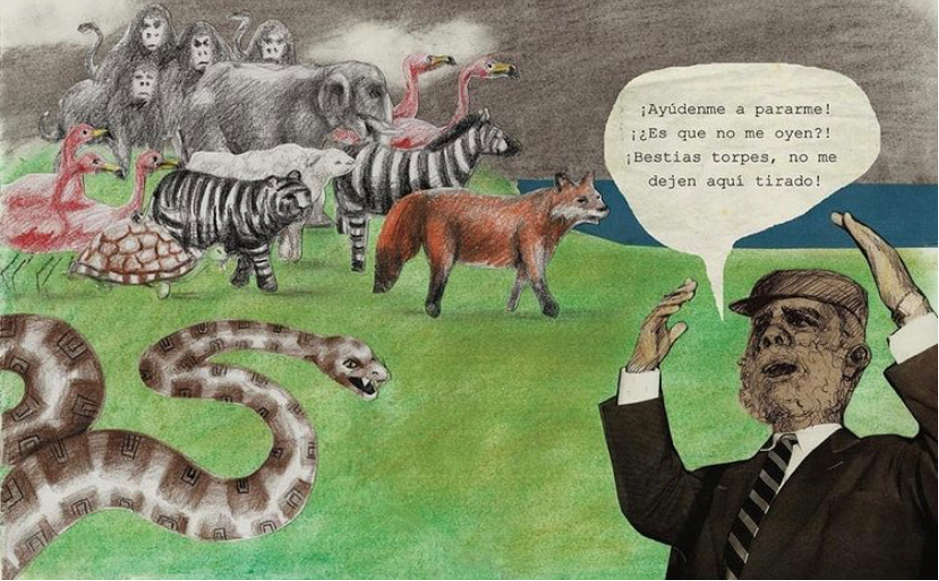

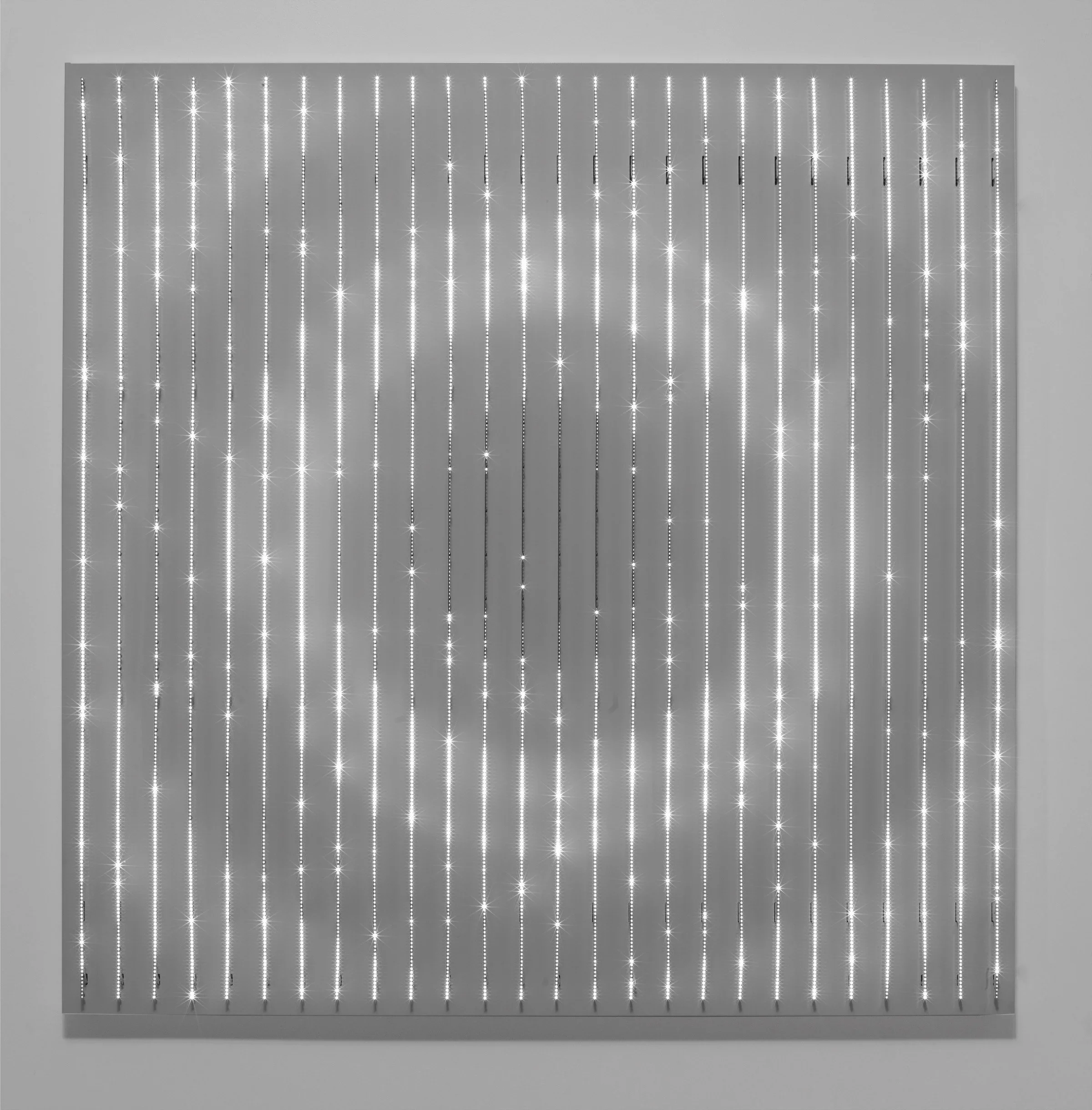

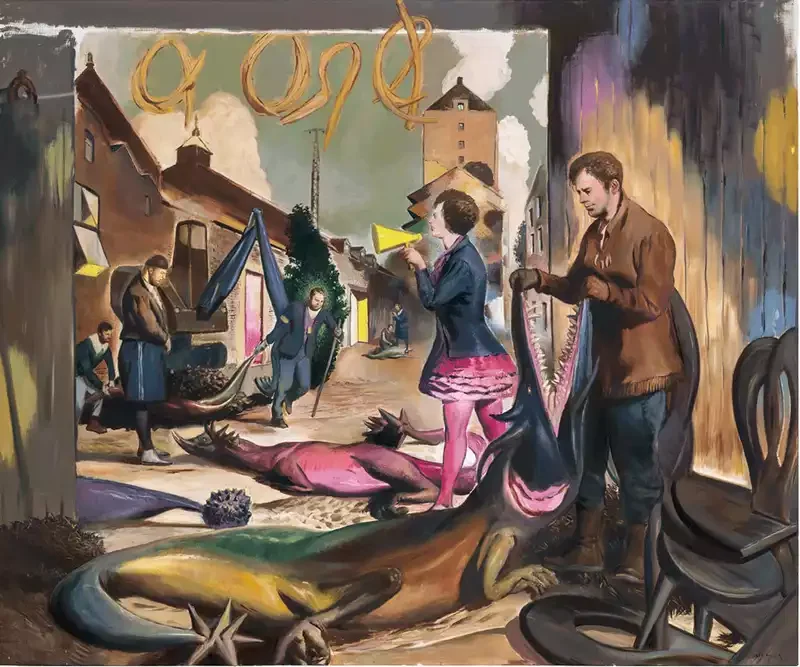

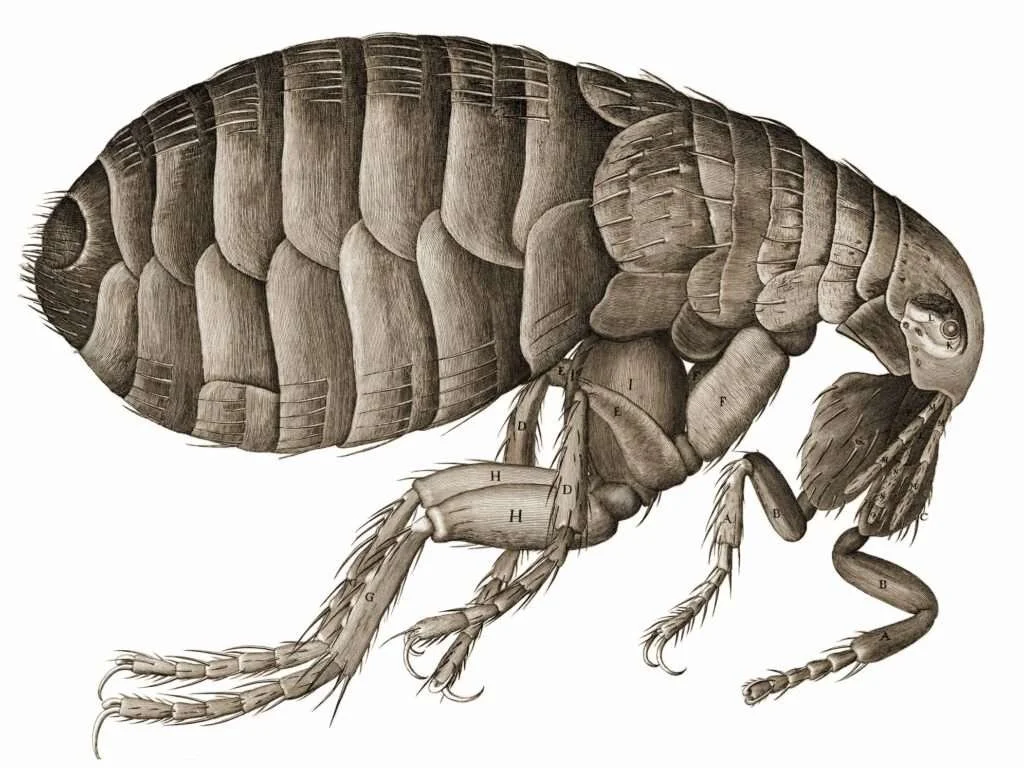

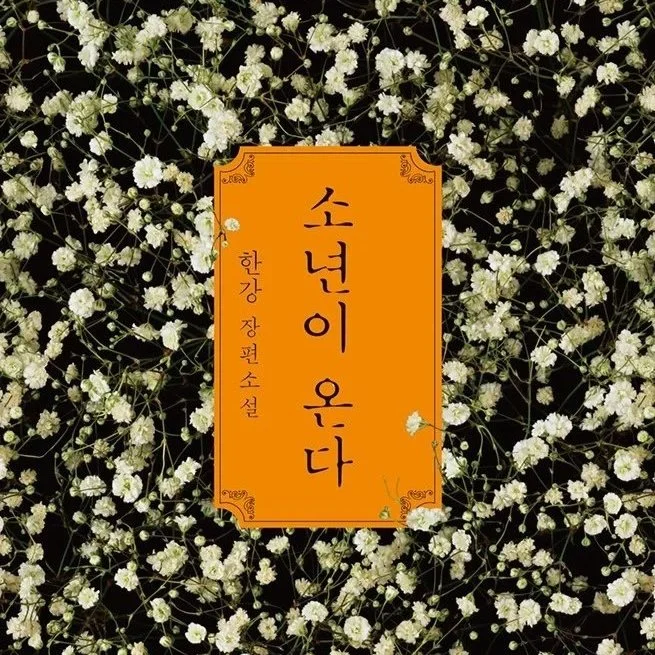

Images from the book-object “Breve relato de una visita al Zoológico” (2017) by Camila Ramírez Lobón.

“Brief account of a visit to the zoo.”

“Good day mister Ram!” “How did you get in, kid? Didn't you see the sign? Get out of here as soon as possible!”

“Why do they keep these poor animals imprisoned? They would be happier running free in the wild.” “What do you say, kid? How could they be imprisoned, if animals have no conscience.”

"Help me stand up! Can't you hear me? You clumsy beasts, don't leave me lying here!"