The Value of Truth

/What is the relationship between truth and value? This essay will determine this relationship, and by doing so, it will claim that a critique of value is of essence.

The concept of value hinges on the condition of scarcity. Because we are spatiotemporal beings, we have to prioritize. We cannot do everything, or be everywhere. We have to rank our priorities, assess trade-offs. In brief: we must evaluate. In economics lingo, this fundamental human condition is analyzed in terms of opportunity cost: the opportunity cost of a decision is the next best option, the one you had to sacrifice in order to pursue the best. You are limited and therefore you must make choices. This the logical precondition of the activity of evaluation and thus of the concept of value. Opportunity cost has a specific relation to price on markets: on a perfectly competitive market, opportunity cost and price match. In the words of the extraordinarily influential economists Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus in their joint textbook: "In well-functioning markets, when all costs are included, price equals opportunity cost".[1]

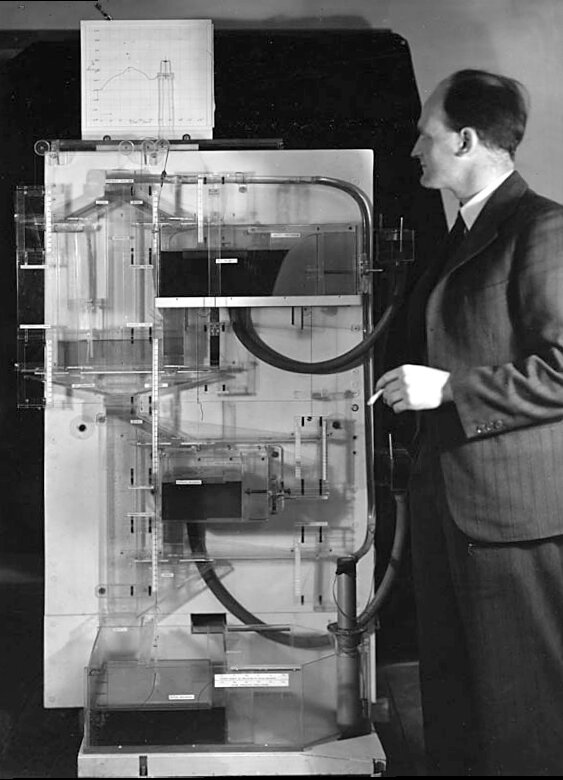

Bill Phillips was an LSE economist known for the Phillips curve and he developed MONIAC, the analog computer, shown here, that modeled economic theory with water flows.

In a market economy, then, a fundamental human condition is used in order to determine how the economy should be organized. Individual priorities and evaluations meet one another in the constant negotiations on the market. On an aggregate scale, these evaluations and negotiations fuse into market price. This price is the fundamental source of information on the market. For example, if people in general want more bread, bread will be sold out in the shops. The sellers will notice the increase in demand and raise the price in order to gain some extra money, because they, as free economic men, are rational and self-interested. Increased price is an incentive for producers to increase production. And so on. In short, our evaluations order production and distribution through price signals. This is the free market. "Free" both because it presupposes that we are free to make individual evaluations, and since if it works we will need no despotic higher power to order the economy.

Just in case anyone wonders, I do not believe that the free market is all that free. You all know the common critiques of this freedom, and I agree with many of them. That, however, is besides my point here.

This supply-and-demand theory was developed in the late 19th century in what is often called the marginal revolution. The peculiar name has its explanation: it is called marginal since it developed the analytical tool of marginal utility. If the total utility of food for me is to keep me alive, the marginal utility of the last unit of food will vary with circumstances. In a famine, the last unit of food will be dear; in a situation of excess, it will be worthless since one can only eat so much before it goes bad. In this way, the marginalists were able to solve the value paradox: why is fresh water, so essential to survival, free or almost free whereas diamonds are expensive? The answer is that the marginal utility of fresh water hardly even exist in the minds of many of us, at least as long as we have fresh water in abundance. The marginal utility of diamonds, however, hardly drops at all. Diamonds are scarce and they don’t go bad: you can never have too many diamonds. Needless to say, the value paradox will have to be rephrased if, or perhaps rather when fresh water becomes increasingly scarce.

Before the marginal revolution, it was often assumed that economic value in one way or the other was present in a commodity due to processes of production, labor being an important factor. Value was, so to speak, objective, although its nature was highly contested. The marginalist value theory is, to the contrary, subjective. It seems to me as though the marginalists in a Kantian style said: maybe we can never know objective value, and maybe that is not even interesting – what is interesting is how people evaluate. We can use price as a signal of people’s evaluations, and let it organize production and distribution of resources autonomously. We no longer need to venture in to the hazy regions of truth in order to know how to order communal life.

Of course, that is not at all what they said. They believed that the supply-and-demand theory of value was true. Still, one of the fore-runners, Hermann Gossen who is known as the first to develop a general theory of marginal utility, viewed himself a Copernican revolutionary.[2] Just like Immanuel Kant did. Why the reference to Copernicus? They switched perspectives, put in the center that which had previously been thought to be peripheral. Economics (or human knowledge for Kant) was now to revolve around the subjective human outlook. Let me thus press the analogy between the marginalists and modern philosophy after Kant: the marginalists dropped the question of value-in-itself (the noumenal sphere of value) and turned to value-for-us (the phenonomenal sphere).

Curiously, the revolution of the marginalists, that is, their breakthrough, happened around the same time as socialism gained ground. For the first time in the history of a substance value theory, usually labor theory of value, the value derived from production processes was understood from the perspective of those that actually did the labor. At exactly that historical point, the labor theory of value was dropped from the germinating science of economics. Even more curiously, in claiming this I am not citing Marxist materialist historiography, but mainstream economics: “It was the rise of Marxism and Fabianism in the 1880s and 1890s that finally made subjective value theory socially and politically relevant; as the new economics began to furnish effective intellectual ammunition against Marx and Henry George, the view that value theory really did not matter became more difficult to sustain.”[3] Mark Blaug is accompanied by Margaret Schabas, decidedly less mainstream, who in her biography on one of the marginal revolutionaries writes: “Marginalism was advanced in the 1870s and 1880s as a means of discrediting socialism and thus meshed perfectly well with current government policies”.[4]

This ideological coincidence notwithstanding, the theory of the marginalists and thereby the logic of the market can be seen as a way to respond to the epistemological cruxes of modernity. It is far too implicated in real epistemological concerns to be dismissed as ideology pure and simple, though its astonishing success should be interpreted through the lens of class interest. After all, this is the theoretical basis for neoliberalism. The theoretical framework that has evolved on the basis of the discoveries of Gossen and his likes, the general equilibrium theory, is the main motivation for implementing free market policies. This theory, however, has no basis in any real economy. For about half a century, it has over and over been shown to be fundamentally flawed.[5] Yet, in its wake, the market economy, we live: according to this order we work, sell and buy. Thus, as I said, ideology clearly matters here. But again, let us not dismiss the theory in its epistemic ambitions solely on the basis of the havoc wreaked in its unfortunate political success. I believe it to be of essence to understand the relationship between this theory that places evaluation at the heart of the order of things and the truth that retracts from our modern lips and minds.

In the light of the turn towards subjective evaluations as the main determining factor in organizing society, one can see that there is nothing banal or deceptive about post-truth and fake news, the immense popularity of trickster figures such as Donald Trump, the systematic questioning of truth from places such as Kreml. Rather, this tendency of truth’s precariousness seem to reflect a complex of interrelated material and theoretical problems in modernity. We all hang suspended over the abyss where Truth once grounded us.

The countermove that is commonly proposed to post-truth and fake news is often asserting the factualness of matters. But facts must be evaluated to gain ground in a world where knowledge is no longer an intimate relation with Truth. The countermove that is commonly proposed to the perceived nihilism of the market is to assert true values. But to focus on true values instead of subjective evaluation is but the flipside of the logic of value of the market. Neither value nor evaluation is comprehensible without the other.

What we need, instead, is a critique of value. If Truth exists it cannot be a value, and it cannot have value. If Truth exists, it cannot be subjected to evaluations to determine its quality.What we need is to hold thought as subject to Truth, rather than the other way around. If philosophy is about thinking with, and against, the dead and the living, a theological critique of value consists in opening thought up to a Truth that can transform us. We must recognize the traces of truthfulness in the entangled confused mess of this world, and follow those traces towards a Truth that is still beyond our grasp, but that hovers, just barely visible, by the horizon. We moderns are ungrounded, but that should not make us fear and cry for more stable ground, as those do that talk about returning to the gold standard, or returning to traditional values. Suspended as we are, we are not falling: the gravitational force of Truth is exercised from above and beyond.

Rosa

[1] Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, Economics, 19. ed. (Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2010), 140.

[2] For the original edition of his groundbreaking work Entwickelung der Gesetze des menschlichen Verkehrs und der daraus fliessenden Regeln für menschliches Handeln, published in 1854, see https://books.google.se/books?id=BzFGAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA231&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

[3] Mark Blaug, Economic History and the History of Economics (Brighton: Wheatsheaf, 1986), 216.

[4] Margaret Schabas, A World Ruled by Number: William Stanley Jevons and the Rise of Mathematical Economics (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1990), 137.

[5] See e.g. Frank Ackerman, Alejandro Nadal, and Kevin P. Gallagher, The Flawed Foundations of General Equilibrium Theory: Critical Essays on Economic Theory (London and New York: Routledge, 2004).