On the Metaphysics of the Flea — Gustav Radbruch, 1916

/“On the Metaphysics of the Flea”, which we publish as the third part in our series of texts on the Lord of the Flies (the other two texts have not been translated to English), was written in 1916 in the midst of the First World War by the jurist and legal philosopher Gustav Radbruch (1878–1949). Radbruch was then serving as an officer in the German army despite his pacifist convictions. Military service was for him a moral duty – a way of showing solidarity with "ordinary people", who in all wars are transformed into cattle sent to slaughter.

Radbruch survived the war and became one of the twentieth century's most influential legal philosophers. During the Weimar Republic, he served as Minister of Justice for the German Social Democratic Party; we will return to his legal philosophy with a new post in a couple of weeks. The Nazi seizure of power in 1933 shattered everything in his life: the new democracy that emerged from the ruins of the First World War was abolished, the socialist achievements he had fought for were dismantled, he lost his professorship, was forced to live in inner exile in Heidelberg, and survived the death of his two children during the Second World war. After 1945, he formulated the famous Radbruch Formula, which states that a law ceases to be valid if it is so profoundly unjust that it violates fundamental principles of justice. This was his answer to how one can resist laws that enable abuses in the name of justice.

Radbruch’s critique of unjust law cannot be separated from the distinctive perspective that characterizes “On the Metaphysics of the Flea”. He likely wrote the text as a reflection on how fleas and lice spread the bacterium Bartonella quintana, which caused trench fever among soldiers. During the war Radbruch became religious – but in his doubting, Socratic way. For him, the divine became a means of questioning this world and its values, a world in which fleas and lice are seen only as something that must be exterminated.

In the text, he attempts to capture nature's immanent, or perhaps rather transcendent, dignity – a dignity that exists beyond our human judgments about what is useful or harmful and that points toward something beyond the order of values: the invaluable. For Radbruch, a world that has become blind to the invaluable, unable to comprehend that which transcends evaluation, would hardly stop at exterminating lice – before long, it would brand certain humans as vermin to be eradicated.

As mentioned, we will return to Radbruch's critique of values in a future post. For those eager to read more about Radbruch, I recommend this article on Hans Barion and Gustav Radbruch regarding the end and nature of law. A more comprehensive discussion of Radbruch's legal relativism and critique of the order of values can be found in the book The End of Law: Political Theology and the Crisis of Sovereignty, recently made available as open access by Routledge.

Mårten Björk

On the Metaphysics of the Flea

The professor – for the time being a reservist – sat deeply concentrated in the trench, with his unbuttoned shirt lifted toward the setting sun. When he had concluded his inspection, he set down the results of his reflections in the following manner:

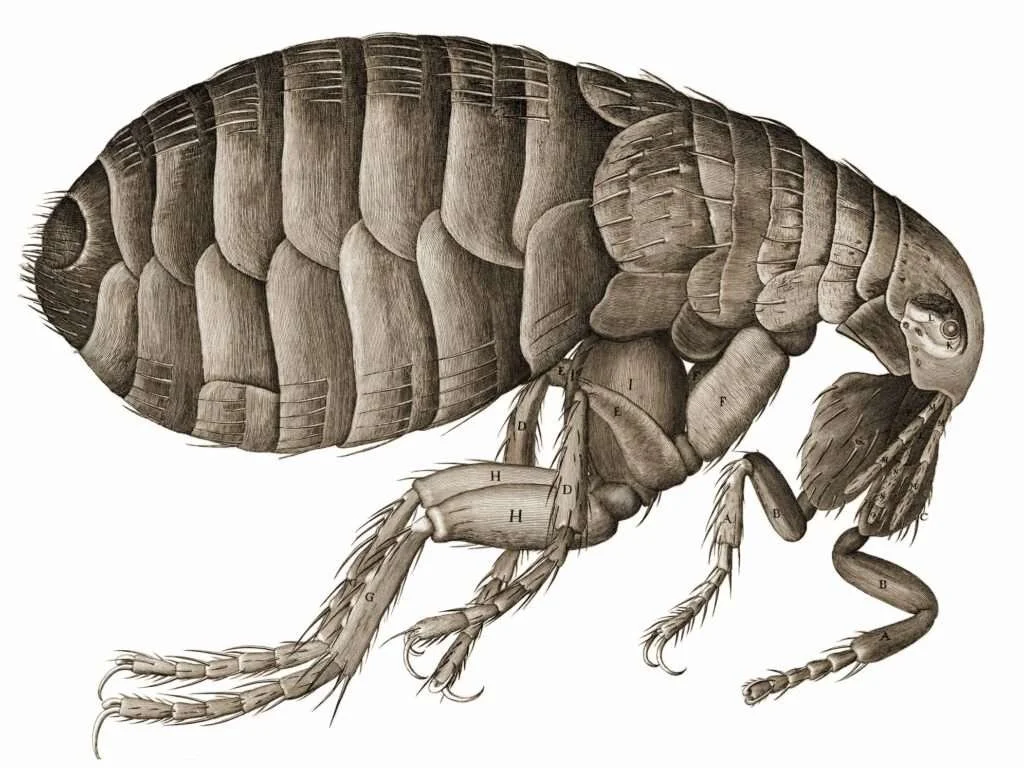

If the task of metaphysics – or if one prefers, of the philosophy of religion – is to determine each thing’s place, even that which seems most worthless, in the all-encompassing realm of values, then one must also grant to the cause of this now week-long torment an ultimate value, an ultimate justification and explanation. And indeed: medieval thinking has also, with clear lines, inscribed the flea into its worldview. The legends would undoubtedly offer rich and varied material for a learned treatise on the flea and its kind as signs and instruments on the path to holiness. But since one cannot reasonably expect to find the Bollandists’ monumental work on the saints in a soldier’s traveling library, a single example must suffice here:

Of Saint Ivo of Kermartin – to whom legal clerks and court assessors owe particular veneration as the patron saint of the legal profession – it is told that he never tried to kill the lice that often plagued him. On the contrary, he lovingly offered them the folds of his garment as a place where they could find nourishment and multiply. Contempt for the body as the wretched earthly vessel that thereby separates the soul from her heavenly home can hardly be expressed more clearly than through this repulsive image: one’s own body as a lightless refuge for crawling vermin, which on their poisoned paths leave behind an itching leprosy.

Thus, the flea became, in the Middle Ages, part of that force that always wills evil yet always creates good: a small bearer of dignity, bound to the Lord of rats, bedbugs and lice, to the god of flies, to great Satan himself. And if Mephisto is permitted to appear as a fool before the Highest throne – ultimately deceived and serving the good powers against his will – then we can imagine in his retinue a small mobile legion with biting humour and, according to the poet's testimony, a brilliant star: our Master the Flea.

But to the flea's – and alas, also to our own – misfortune, it has through the secularization of modern culture irrevocably lost its metaphysical dignity. Our age's this-worldly religion teaches us to regard the world as humanity's sole workshop, the body as the soul's beautiful home, and the nourishing earth as something we should love deeply. That which is hostile to the life of body and soul can in this view no longer be assigned any positive value.

Indeed: great pain as well as great spiritual distress, great guilt – all that experiential material which elevates us by crushing us – finds its place even in this worldview. The pathos that accompanies it is ultimately the most vital aspect of life. But with colds, toothaches and migraines, with irritation and small vexations, with all the minor sufferings that belong to human life, which the once celebrated French caricaturist Grandville aptly embodied as fantastical figures of ghostly vermin, and thus also with the flea itself, our age's this-worldliness cannot cope. Since the borrowed lustre from his little courier has been extinguished together with the hellish fire glow of this world's prince, every possibility of granting the flea any pathos seems to have vanished.

Friedrich Theodor Vischer's Auch Einer shows in a witty and entertaining way how, alongside the world, "the world of trifles" and "the malice of objects" lets its trollish essence rage – something one can only overcome through humour. But in the comic, the thing's vexation is indeed transformed into the pleasure of its aesthetic representation; however, matter's friction is not transformed into a driving force for the active will. In sharp contrast to the religious attitude, the humorous stance implies a nihilistic withdrawal from attempts to discern a thing's meaning and significance for our active life.

And so the result of our philosophical study of the flea would be this: that the flea can indeed be incorporated without difficulty into the worldview of both the laughing philosopher and the ascetic, the martyr and the saint alike – and yet the deeply thinking person still struggles to comprehend the flea's pathos, the tragedy of one afflicted with fleas.

You who are protected by our arms: it falls to you to grant us one or the other – either a metaphysics of the flea, or an effective means for its extermination. For – thus concluded the philosopher, while standing watch by the ever-dimming glow of the carbide lamp in his trench – if something cannot be thought and therefore in a more profound sense lacks reality for the philosopher, then this thing's unreality must be made visible even to the less discerning eye – precisely through its extermination.

Gustav Radbruch